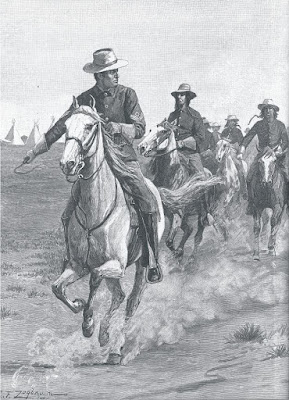

US Indian Scouts were an official branch of the US Military from 1865 to about 1950. Indian Scouts also had their own guidons, military flags.

The Spy And

The Wolf

Tunwéya Na Šuŋgmánitu Tĥáŋka

By Dakota

Wind

GREAT

PLAINS – There were two kinds of scouts on the Great

Plains in the nineteenth century. One kind consisted of Indians

who enlisted in the US

military as members of the US Scouts, an official branch of the US US

The other

kind of scout served the native people by going out ahead of the main camp and

watching for enemies, guiding the camp to the best campsites, and searched for

game. The essential qualifications of the scout included truthfulness, courage,

intuition, and a thorough knowledge of the landscape.

Native men

who enlisted as US Scouts did so for a variety of reasons. Some enlisted as a

means to avenge themselves on an enemy tribe, but others did so out of the

desperate need to feed their families.

"The Buffalo Hunt Under The Wolf Skin Mask" by American artist George Catlin. Indian scouts sometimes employed the wolf skin as a means to sneak up on game or enemies.

Native men,

so far as Lakĥóta men are concerned,

were selected by council and gathered by the headmen for council. At the

council, they would pray, smoke, and talk about the importance of the occasion.

The chief and council spoke about the benefits for the entire camp upon

success, and dire consequence upon defeat. The scouts were told to be wise as

well as brave, to look not only to the front but behind, up as well much as to

the ground, to watch for movement among the animals, to listen to the wind, to

be mindful when crossing streams, to not disturb any animals, and to swiftly return

to the people with any information.

Lakĥóta scouts, weren’t selected for

their fighting prowess, nor were they necessarily warriors. The scout party was

selected for each man’s keen eyesight and a man’s reputation for shrewd cunning

and quick vigilance.

The Lakĥóta have sayings for mindfulness or

awareness. In an online discourse with Vaughn T. Three Legs, Iŋyáŋ Hokšíla (Stone Boy), enrolled

member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and radio personality on KLND 89.5 FM, and

his čhiyé (older brother) Chuck

Benson, they shared the phrase Ablésya máni

yo, which means, “Be observant as you go,” but observation also implies

understanding.

"Comanche War Party, Chief Discovering Enemy And Urging His Men At Sunrise" by George Catlin, 1834. Note: the chief meets the two scouts at the crest of the hill.

Cedric

Goodhouse, a respected elder and enrolled member of the Standing Rock Sioux

Tribe, offered Ĥa kíta máni yo, which

means, “Observe everything as you go.” He also put before this writer the

phrase Awáŋglake ománi, or “Watch

yourself as you go around.” Lastly, Cedric shared the philosophy Taŋyáŋ wíyukčaŋ ománi, “Think good

things as you go around.”

The late Albert

White Hat, a respected elder, teacher, and enrolled member of the Rosebud Sioux

Tribe, often shared the phrase Naké nulá

waúŋ, “Always prepared,” or “Prepared for anything,” but this preparedness

also reflects a readiness in spirit to meet the Creator too.

Each of these sayings were things practiced daily in camp and on the trail, then and today.

Before

starting out, the scout’s relatives, or the camp’s medicine people offer

prayers of protection, for the sun and moon to light the way, for the rain to

fall sparingly, for the rivers and streams to offer safe passage, for the

bluffs to offer unimpeded views, and for gentle winds. All of nature is

petitioned to assist the scout to the people’s benefit.

When the

scouts set out, only two were permitted to go in the same direction. A larger

scout party could see and report no more information than two. A larger party

would certainly be discovered more easily by the enemy.

The scout,

whether he was a US Indian Scout or a Lakĥóta

scout, would take with him a small mirror or field glass, invaluable tools made

available in the early fur trade days. A scout would signal with his mirror a

pre-determined set of flashes for the main camp to interpret and prepare long

before his return. A tremulous series of flashes might indicate that the enemy

was seen.

An online search for "mirror," "bag," and "Sioux," brought this image up. This type of mirror bag could easily be modified to be worn around the neck.

As the scout

approached the main camp, near enough for vocal communication, he might let

loose a wolf howl, again, to indicate that the enemy was seen and/or

approaching.

Upon viewing

the flashes and certainly upon hearing the wolf howl, the main camp war chief,

headmen, and warriors would gather in a circle broken by an opening towards the

approaching scout. The scout or scouts entered the broken circle and completed

it, where they shared the news.

Captain

William Philo Clark, a graduate of the US Military School, and military scout

under General Crook, observed firsthand or heard from native authorities of a

ceremonial ritual upon the scout or scouts return. Clark served in Dakota Territory from 1868 to 1884, and authored “The

Indian Sign Language.” Clark observed that all

tribes observed a return ritual for their scouts.

Basically,

the broken circle is complete when the scout or scouts enter the opening,

whereupon the pipe is offered to the six directions, the war chief or other

headman and scout draw breath on the pipe, and upon the fourth time, the scout

or scouts are debriefed. It was Clark ’s observation

that often enough the ritual was not always practiced. Certainly if there were

an enemy war party fast approaching, ceremony was dropped in preparation for

combat.

The Lakĥóta word for scout is Tuŋwéya, which means “Spy,” “Guide,” or “Scout.”

The sign for scout is simply “Wolf.” Hold the right hand, palm out, near right

shoulder, first and second fingers extended, separated and pointing upwards; remaining

fingers and thumb closed; move right hand several inches to front and slightly

upwards, turning hand a little so that extended fingers point to front and

upward.

The Lakĥóta scout sometimes employed a wolf

headdress to aid in his mission; sometimes they even carried a bone whistle to

aid in alerting the camp.

In English,

the word spy implies a clandestine secrecy; a guide leads people in unfamiliar

territory, and a scout might mean learning basic survival skills or a covert

military reconnaissance. For the Lakĥóta,

tuŋwéya clearly meant spying and reconnoitering

for the camp; they already know their own country and all except the smallest certainly

knew basic survival skills, however they definitely needed to know who else

traveled in their territory.