A view of Crying Hill from above in the 1930s.

Crying Hill:

A Sacred Natural Landmark

Where The Hidatsa Became Two Tribes

Edited by Dakota Wind

Mandan, N.D.

- In 1919, Colonel Alfred Burton Welch, a World War I veteran came to call the

city of Mandan, N.D. home. There in Mandan, Welch began a new life as a store

keeper, he also served as the post master, and founded the El Zagel Shrine. He

spent the remainder of his life in the rolling hills of Heart River country

along the Missouri River valley, and became fast friends with many of the

Indian tribes there.

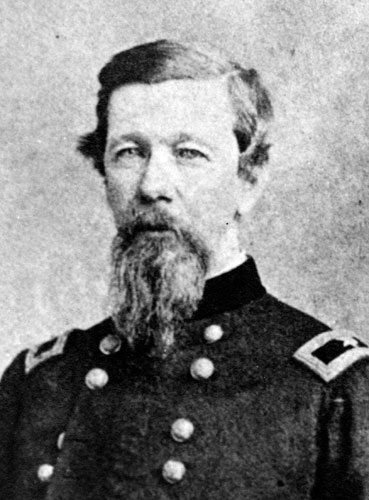

Captain AB Welch, seen here in his uniform from the 1898 Spanish-American War.

Welch became good friends

with Chief John Grass. Grass was a distinguished Sihásapa Lakȟóta leader and veteran of the Sioux campaigns of the

1870s such as the Little Bighorn. Grass was known to the Lakota as Matȟó WatȟákpA, or Charging Bear. He had

attended the Carlisle Indian School and became fluent in English to help his

people fight the government in the new battlefields, the courtrooms. In March

1913, Grass adopted Welch as his son and bestowed on him Grass’ own name of

Charging Bear.

While Welch lived in Mandan

he took in all the lore about the site and more, and recorded as much as he

could. One of those site stories he recorded was about the village and people

who lived in the Mandan village along the Heart River near to Crying Hill.

Andrew Knudson painted this scene of the Corps of Discovery entering Black Cat's village near Knife River. A similar village would have graced the banks of Heart River below Crying Hill. That village was known to the Mandan as Large And Scattered Village.

The Mandan Indians have

lived along the Upper Missouri River for about a thousand years and longer if

you take into account their emergence story south of Mandan.

According to Welch, or the

stories he attributed to the Hidatsa, Crying Hill is where the Hidatsa split

into two distinct tribes. Welch uses the term Gros Ventres to name the Hidatsa. Here’s the story, Feb. 24, 1925:

The Gros Ventre were divided into two bands, and each

of these bands followed their own chiefs. One starving winter-time they were

reduced, by the absence of game and the failure, or destruction, of their

crops, to eating the red seed pods of the wild rose bushes.

But, at last, through the prayers of a holy man among

them, one lone, rogue buffalo bull, lean and staggering, wandered close to the

village. He was chased and fell in the exact middle of the Heart River. Upon

being dragged to the shore, it was decided that the meat should be divided in

two equal portions, each band obtain the same amount of meat, bone and

hide. When the division was made, one band was aggrieved and claimed that

the other party had obtained the fatty portion of the stomach, while they had

only the lean part.

The aggrieved band then decided that they would leave

the other and go into a country which they would discover, and where they would

be their own hunters and use their kill as they saw fit to do. Consequently

this band did leave, traveled southwest into the country west of the Black

Hills and east of the Big Horn Range, which territory they secured and where

they have maintained themselves ever since that day.

These are the people known today as the Crows. They

frequently come to visit the Gros Ventre; speak the same language and accept

each other as cousins or relatives, but the real Gros Ventre call the crows the

“Jealousy People,” on account of the separation, long ago.

Crow Indians Firing Into The Agency by Frederic Remington.

A variation of the story

about the separation of the Hidatsa into two tribes came a few years earlier by

way of Joe Packineau, Dec. 3, 1923:

“Crow Indians are Gros Ventre. I will tell you

how it came about that they do not live together now. “That Indian village site

in Mandan, we call it “Tattoo Face.” It is not Mandan village, but Gros

Ventre or Hidatsa.

“There were two brothers born in that place a long

time ago. One had a tattoo mark on his face like a quarter moon. It started on

the cheek and ran down across the chin and up on the cheek on the other side of

his face. So the people called him Tattoo Face. He became a very

famous man among the Gros Ventre. His brother was all right, and he was

named Good Fur Robe. He also became a very great man and a wise man.

“Good Fur Robe was the one who had the corn seeds

first. He gave one grain to each person and told them how to plant and

look after the plant. Tattoo Face had tobacco before anyone else.

“Now the best part of a buffalo is his paunch. It is

nice to eat. One time there was one buffalo which they killed right in the

river there. He dropped dead in the middle of the Heart River when he was

killed. The people drew him out for they were hungry. Good Fur Robe

was the biggest chief, so he took the paunch when they divided the buffalo up

between the two bands.

“That made [the] Tattoo Face people mad so that band decided

that they would go away. They did go, and made their home in the country west

of the Black Hills after that time.

“People call that people Crows now. But the

Hidatsa do not. We call them “The Paunch Jealousy People.”

So the place where these people separated from the

Hidatsa, is the Heart River at the Crying Hill (or Tattoo Face Village) which

was Gros Ventre. The Mandan lived there too after that, I think.”

Crying Hill is located

within the city of Mandan, ND. In 2003, Patrick Atkinson purchased Crying Hill

in efforts to save the heritage site from further development. Read about

Atkinson’s efforts to preserve Crying Hill.