Whitestone Hill, this image appeared in Harper's Weekly, based on a pencil drawing by Gen. Alfred Sully.

Terrible Justice, A Book Review

No Detail Too Grim Left Out

By Dakota Wind

Chaky, Doreen. Terrible Justice: Sioux Chiefs and U.S. Soldiers on the Upper Missouri, 1854-1868. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. 2012. $39.95 (hardcover). 408 pages. Illustrations, maps, photographs, bibliography, and index.

Chaky’s Terrible Justice begins with the Ash Hollow conflict of 1854, as settlers migrated across the Great Plains to better lives on the west coast or in the Rocky Mountains. Her research was sparked after participating in an archaeological survey at Fort Rice, and she soon realized that as much as the story of adventure belonged to the soldiers, it was a story that ultimately belongs to the Sioux. She was not satisfied that so little was published about the military’s role in Manifest Destiny there at Fort Rice and across the plains.

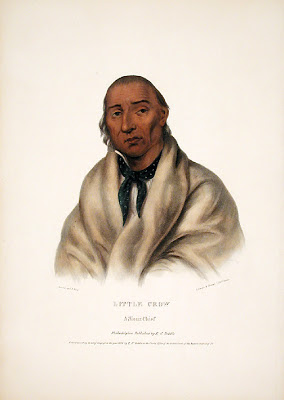

An example of an outstanding feature in Terrible Justice is Chaky’s use of Little Crow’s actual name, which is Taóyate Dúta (His Red Nation), and her continued use of his real name throughout her book. She doesn’t mince words in her description of the punitive military campaigns – Generals Sibley and Sully were sent to make war, take prisoners, destroy food resources, and secure Dakota Territory for white settlement.

Chaky carefully constructs the 1863 Sibley campaign on the orders of General Pope and his orders to secure Dakota Territory from President Abraham Lincoln. Sibley’s march is an invasion, and the conflict between the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ (the Great Sioux Nation) and Sibley's command began when his campaign left from Camp Pope on the Minnesota River, not when a young man from the band of Íŋkpaduta (Scarlet Point) shot and killed Surgeon Weiser.

Terrible Justice isn’t an apologist’s narrative. Chaky describes in great detail the gory violence and destruction committed by men, native and non-native; scalps taken by soldiers and warriors. But, she draws close when she includes brief remembrances of Pvt. Phebus, Sgt. Martin, and acting Gov. Hutchinson, several years after the Whitestone Hill massacre.

Federal “Indian Policy” has always been one of dispossession and displacement. As settlers advanced west into Indian Country, tensions erupted in an escalating conflict until the military came in to secure the peace by forcing first nations to sign treaties (land cessions and reservations). Treaties were generally signed by a majority of grown men, sometimes not even by that (ex. Treaty of New Echota).

The Sibley-Sully campaigns were pre-emptive. The Yanktonai, who, at that time yet lived in their homeland, were killed, imprisoned, and forced west across the Missouri River without ever signing a treaty to cede their lands. The land between the Missouri River and the James River is still unceded Yanktonai territory.

Chaky signed my copy, “Dakota, I hope I’ve represented the Sioux properly with this book. I enjoyed doing it very much. Doreen Chaky, 7/28/13.” It’s a book that’s not hard to read, but it’s straight content and elaborate description make it hard to read. These are my people. Chaky began her narrative that this was “the story of the Sioux.” A quick review of her bibliography reveals six recognizable works by first nations, and one hopes a second edition of Terrible Justice would draw on more the surviving oral tradition.

Recognizing that there are many, many books available for purchase on the subject of the Little Bighorn conflict, Chaky brings her work to a tidy close, by barely mentioning that fight (one sentence). Wounded Knee receives no mention. That’s all right, not every history book about the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ needs to include that tragedy. Chaky focuses on the conditions of peoples, native and settler, of the Great Plains.

It's a good book. Go get yourself a copy. The maps are a great visual aid.

Dakota Wind is an enrolled member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. He is currently a university student working on a degree in History with a focus on American Indian and Western History. He maintains the history website The First Scout.

It's a good book. Go get yourself a copy. The maps are a great visual aid.

Dakota Wind is an enrolled member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. He is currently a university student working on a degree in History with a focus on American Indian and Western History. He maintains the history website The First Scout.