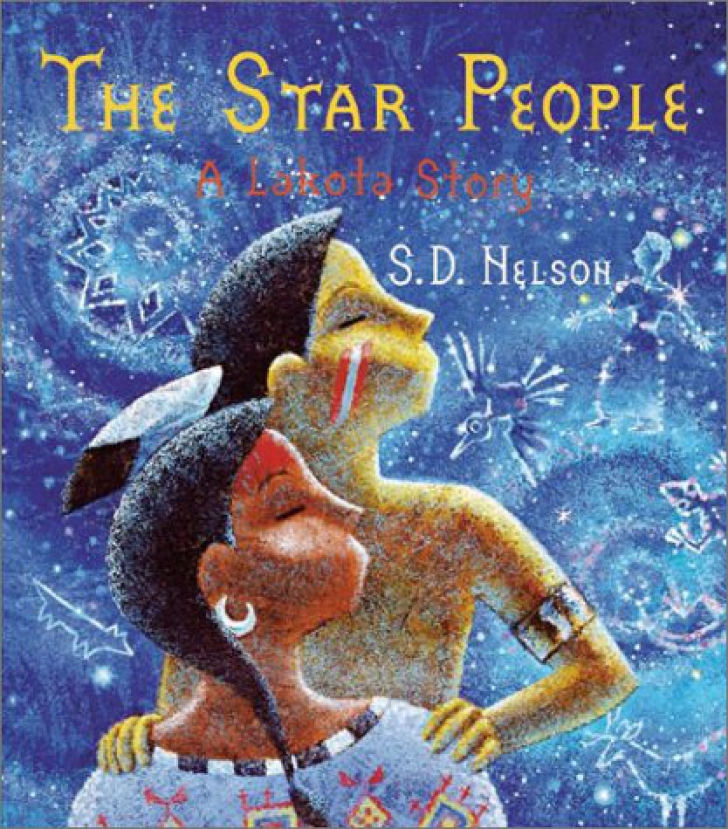

A depiction of the Battle of The Little Bighorn by Kicking Bear.

Horned Horse's Account

The Battle of the Little Bighorn

By Dakota Wind

BISMARCK, D.T. (N.D.) - In Chapter 2 of Warpath and Bivouac, or Conquest of the Sioux, by John Finerty, Finerty compares the Battle of the Little Bighorn to the Battle of Thermopylae in ancient Greece over two thousand years ago. Finerty also compares General Custer to the biblical hero Samson, “both were invincible while their locks remained unshorn.”

In Jessie Reil’s

article, Custer’s Stand Mattered for Victory, which appears on the website http://www.custerwest.org,

Reil compares General Custer’s passing, also, to that of Samson’s death. Both “pulled the house down” on their enemies

and lost their lives for it.

Here follows an

excerpt from Finerty’s book, chapter XIV.

Horned Horse, an old Sioux chief, whose son was killed early

on in the fight, stated to the late Capt. [William] Philo Clark, after the

surrender of the hostiles, that he went up on a hill overlooking the field to

mourn for the dead, as he was too weak to fight, after the Indian fashion. He had a full view of all that took place

almost from the beginning. The Little

Bighorn is a stream filled with dangerous quicksand, and cuts off the edges of

the northern bluffs sharply near the point where Custer perished. The Indians saw the troops on the bluffs

early in the morning, but, owing to the abruptness and height of the river

banks, Custer could not get down to the edge of the stream. The valley of the Little Big Horn is from

half a mile to a mile and a half wide, and along it, for a distance of fully

fifty miles, the mighty Indian village stretched. Most of the immense pony herd was out grazing

when the savages took the alarm at the appearance of troops on the heights. The warriors ran at once for their arms, but

by the time they had taken up their guns and ammunition belts, the soldiers had

disappeared. The Indians thought they

had been frightened off by the evident strength of the village, but again,

after what seemed quite a long interval, the head of Custer’s column showed

itself coming down a dry water course, which formed a narrow ravine, toward the

river’s edge. He made a dash to get

across, but was met by such a tremendous fire from the repeating rifles of the

savages that the head of his command reeled back toward the bluffs, after

losing several men, who tumbled into the water, which was there but eighteen

inches deep, and were swallowed up in the quicksand. This is considered an explanation of the

disappearance of Lieutenant Harrington and several men whose bodies were not

found on the field of battle. They were not

made prisoners by the Indians, nor did any of them succeed in breaking through

the thick array of the infuriated savages.

Horned Horse did not recognize Custer, but supposed he as

the officer who led the column that attempted to cross the stream. Custer then sought to lead his men up to the

bluffs by a diagonal movement, all of them having dismounted, and firing,

whenever they did, over the backs of their horses at the Indians, who by that

time crossed the river in thousands, mostly on foot, and had taken the General

in flank and rear, while others annoyed him by a galling fire from across the

river. Hemmed in on all sides, the

troops fought steadily, but the fire of the enemy so close and rapid that they

melted like snow before it, and fell dead among their horses in heaps. He could not tell how long the fight lasted,

but it took considerable time to kill all the soldiers. The firing was continuous until the last man

of Custer’s command was dead. Several

other bodies besides that of Custer remain unscalped, because the warriors had

grown weary of the slaughter. The

water-course, in which most of the soldiers died, ran with blood. He had seen many massacres, but nothing equal

to that. If the troops had not been

encumbered by their horses, which plunged, reared and kicked under the

appalling fire of the Sioux, they might have done better. As it was, a great number of Indians fell,

the soldiers using their revolvers at close range with deadly effect. More Indians died by the pistol than by the

carbine. The latter weapon was always

faulty. It “leaded” easily and the cartridge

shells stuck in the breech the moment it became heated, owing to some defect in

the ejector. It is not improbable that

many of Custer’s cavalrymen were practically disarmed, because of the

deficiency of that disgracefully faulty weapon.

If they had been furnished with good Winchesters, or some other style of

repeating arm, the result of the battle of the Little Big Horn might have been

different.

What happened to Custer, after he disappeared down the north

bank of the river, has already been told in the words of Curly and Horned

Horse. Not an officer or enlisted man of

the five troops under Custer survived to tell the tale. The male members of the Custer family, George

A., Colonel Tom and Boston,

were annihilated. Autie Reed, a young

relative of the General, who, like Boston Custer, accompanied the command as

sightseer, was also killed. Mark

Kellogg, of the St. Paul

and Bismarck Press, the only correspondent who accompanied the Custer column,

nearly succeeded in making his escape.

The mule he rode was too slow, however, and he was finally overtaken and

shot down. Had he succeeded in getting

away, his fame would have rivaled that of the explorer, Stanley.

Reno

crossed the Little Big Horn, accompanied by some of the scouts, and charged

down the valley a considerable distance.

He finally halted in the timber and was, as he subsequently claimed,

attacked by superior numbers. He

remained in position but a short time, when he thought it advisable to retreat

across the river and take up a position on the bluffs. This movement was awkwardly executed, and, in

scaling the bluffs, several officers and enlisted men were killed and

wounded. The Indians, as is always when

white troops retreat before them, became very bold, and succeeded in dragging

more than one soldier from the saddle. Captain

De Rudio, an Italian officer, exiled from his country for political reasons,

and a scout, unable to keep up with Reno’s main body, concealed themselves in

the brush, and the Indians passed and repassed so close to them that they could

have touched the savages by merely putting out their hands. They were fortunate in remaining

undiscovered, and joined Reno

on the 27th, after the arrival of Terry and Gibbon.

Col. F.

W. Benteen, new retired and residing at Atlanta,

GA., has, at the request of the

author, given the following statement relative to the movements of his

battalion after parting from the main command:

There was to have been

no connection between Reno,

McDougall and myself in Custer’s order.

I was sent off to the left several miles from where Custer was killed to

actually hunt up some more Indians. I

set out with my battalion of three troops, bent on such purpose, leaving the

remainder of the regiment, nine troops, at a halt and dismounted. I soon saw, after carrying out the order that

had been given me by Custer, and two other orders which were sent to me by him,

through the sergeant-major of the regiment and the chief trumpeter, at

different times, that the Indians had too much “horse sense” to travel over the

kind of country I had been sent to explore, unless forced to; and concluded

that my battalion would have plenty of work ahead with the others. Thus, having learned all that Custer could

expect, I obliqued to the right to strike the trail of the main column, and got

into it just ahead of McDougall and his pack train.

I watered the horses

of my battalion at the morass near the side of the road, and the advance of

McDougall’s “packs” got into it just as I was “pulling out” from it. I left McDougall to get his train out in the

best manner he could, and went briskly on, having a presentiment that I’d find

hot work very soon. Well, en route, I met two orderlies with messages – one

for the commanding officer of the “packs” and one for myself. The messages read: “Come on. Be quick” and “Bring packs;” written and signed

by Lieutenant Cook, adjutant of the regiment.

Now, knowing that there were no Indians between the packs and the main

column, I did not think it necessary to go back for them – some seven or eight

miles – nor did I think it worth while waiting for them where the orders found

me, so I pushed to the front at a trot and got there in time to save Reno’s

“outfit.” The rest you know.

Reno,

Benteen and McDougall, having effected a junction, fortified themselves on the

bluffs and “stood off” the whole Indian outfit, which laid close siege to them,

until the 27th. Several

desperate charges of the savages on the position were handsomely repulsed. The troops, especially the wounded, suffered

terribly from thirst, and during the night a few daring soldiers succeeded in

getting some water out of the river in their camp kettles, at the peril of

their lives. One of those brave men was

Mr. Theodore Golden, then of the 7th Cavalry, and now a resident of Janesville, Wisconsin.

The situation of the closely beleagured troops was growing

desperate, when the infantry and light artillery column of General Gibbon,

which was accompanied by General Terry, came in sight on the morning of the 27th. The soldiers of Reno,

at this inspiriting vision, swarmed out over the rough and ready breastworks,

cheering the heroes of Fort Fisher and Petersburg

vociferously. Many wept for joy and the

chivalrous Terry and the gallant Gibbon did everything in their power to cheer

up the wearied soldiers in their hour of misfortune. The Indians did not attempt any further

attack after the rescuing party arrived.

They, too, were tired out, and had expended a vast quantity of

ammunition. They drew off toward the

mountains, first burning such irremovable impedimenta as remained in their

village. A part of their teepees had

been burned in the fight with Custer.

General Gibbon, after a brief rest, set out to see what had become of

that officer. Reno’s men felt certain that something

dreadful had happened to their comrades, because during the afternoon of the 25th

and the morning of the 26th they had recognized the guidons of the 7th

Cavalry, which the savages were waving in ecstasy of triumph. General Gibbon had to march several miles

before he came upon the field of blood.

The sight that met his eyes was a shocking one. The bluffs were covered with the dead bodies

of Custer’s men, all stripped naked, and mostly mutilated in the usual

revolting manner. The General’s corpse

was found near the summit of the bluff, surrounded by the bodies of his brothers

and most of the officers of his command.

The Indians, had recognized his person, and who respected his superb

courage, forbore from insulting his honored clay by the process of

mutilation. The 7th Infantry,

General Gibbon’s regiment, buried the gallant dead where they fell, marking the

graves of all that could be identified.

Custer’s remains, and those of his relatives, together with those of

most of the officers, have been removed.

The brave General is buried at West Point,

from which he graduated, and on which his glorious career and heroic death have

reflected immortal luster.

General Custer’s body

was mutilated, not nearly to the extent as his brother Tom’s body was – who was

mutilated beyond recognition; a tattoo was the only thing that identified Tom

Custer’s body at all. In fact, several,

out of the 206 other soldiers were not mutilated, and two soldiers, it would

seem, out of respect were not mutilated at all.

One of General Custer’s legs was slashed, an arrow was forced up his

manhood, and his ears were perforated – possibly with arrows or awls.

.jpg)