"Crying Hill," or "Mandan Hill" can be seen in the middle of this photo, the Missouri River down below, city development behind in the distance.

Crying Hill Endangered

Site Overlooks River, City,

Interstate

By Dakota Wind

Mandan, N.D. (TFS) – A hill rolls above

the floodplain where the Heart River converges with the Missouri River. It

divides the city of Mandan from traffic of I-94. It loudly proclaims “MaNDan”

on its east face in bright white concrete lettering; the south face of this

same plateau says the same but with trees spelling the city's name.

It’s the home of the Mandan Braves,

named after the indigenous people who lived there on the banks of the Heart

River as traders, fishers, and farmers. The Nu’Eta, as they call themselves,

could defend themselves when called for as well. They lived in fortified

villages in the Heart River area from about 1450 to about 1781.

Each village had a civil chief and a war

chief to advice and look after their interests. The Nu’Eta were productive and

hard-working. They must have been doing something right; their villages

possessed no jails.

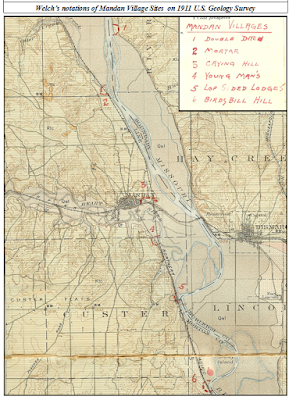

Welch's notations on a 1911 US Geological survey map. Bismarck and Mandan have grown considerably in the hundred+ years since.

The village along the banks of the Heart

River in present-day Mandan, ND was large, with a population of perhaps as many

as 3000. Its identified mainly as a Nu’Eta site, but the Hidatsa claim the

populace as their own. The Hidatsa became neighbors of the Nu’Eta sometime

around 1600 C.E., and inter-married with them over the centuries that today one

isn’t Nu’Eta without having Hidatsa relatives.

This large village was known by many

names. The Nu’Eta called it Large and Scattered Village. The Hidatsa called it

the Two Faced Stone Village for the sacred stone feature atop the plateau

overlooking their village. Crows Heart, a principle leader of the Nu’Eta,

informed Colonel Alfred Welch that that they called the village there in

present-day Mandan, “The Crying Hill Village.” Crows Heart also essayed to

Welch that they called it so because their women went to the top of the hill to

mourn for lost relatives.

Another village there, south of the

Crying Hill Village, called Motsif today, was known by the Nu’Eta as Youngman’s

Village. According to Welch’s informants, the Nu’Eta of both these two villages

would gather together and inhabit a winter camp in the timber on the floodplain

of the Missouri River[1].

According to the late Mr. Joe Packineau,

the Crow separated from the Hidatsa at the Crying Hill Village, adding that the

village was also called the Tattoo Face Village, and further, that it was

Hidatsa, not Nu’Eta. In the time of Good Fur Robe, he had a brother whom they

called Tattoo Face. A hunt concluded with a dead bison recovered from the

middle of the river. Good Fur Robe divided the kill and took the paunch, which

infuriated Tattoo Face and his people, who picked up and moved west. According

to Packineau, the Hidatsa called them not Crow, but “The Paunch Jealousy

People.” Where the Crow broke away from their Hidatsa relatives was at the

Crying Hill Village[2].

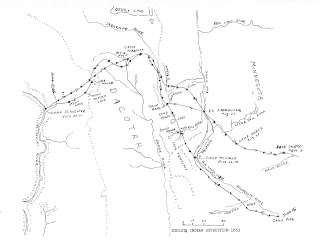

Welch drew this diagram mapping the features of Crying Hill. Visit the Welch Dakota Papers site.

At the top of Crying Hill were stone

features (including a stone turtle effigy measuring twelve feet across), sacred to the Nu’Eta, upon which were images or pictographs, which

changed, and were said to be able to tell the future. One oracle stone in

particular, was said known as the “Two Face Stone.” When diviners gathered

‘round to interpret the stone’s musing for the future, they would lift the

stone, which seemed to them to be very light. Upon putting it down, they would

lift again, and the stone mysteriously weighed more than one could lift. They

called this stone Two Face because of its dual nature, and according to Welch’s

informant, the village below was called “Two Face Village.” Enemy Heart, an

Arikara man, estimated the side of the Two Face Stone to be a diameter of about

18 inches[3], it’s location, at least

in 1912, was lay just east of the Morton County Courthouse in Mandan, ND[4]. Enemy Heart insisted that

the Crying Hill Village’s proper name was Two Face Village.

In the 1870’s, as the city of Mandan developed

on the remains of the Large and Scattered Village, or Crying Hill Village, or

Tattoo Face Village, Two Face Village, homes and streets encroached on Crying

Hill itself. One day, a prospective home owner, took dynamite to the sacred

stone on the hillside of Crying Hill and blew it up[5]. Welch contends that the

greater oracle stone was drilled and split by white settlers for building

stone. One resident, Mr. G.W. Rendon built the basement of his house from

fragments of this holy stone[6].

There used to be a burial ground at

Crying Hill. In 1933, laborers of the city of Mandan were expanding development

of the city for two new houses, and disturbed the graves of eleven Nu’Eta men

and women, including a baby. Col. Alfred Welch was called on to offer his

assessment of the findings, and he estimated that the size of the Crying Hill

Village at about 3000 souls, and was occupied for about 300 years[7], from ~1500 C.E. to about

~1800 C.E. The bodies were hastily buried, possibly due to the haste in which

the survivors departed the Heart River villages in 1781 following the smallpox epidemic

which struck them.

This reconstruction of the 1863 Apple Creek Fight is overlaid on 1850's Warren survey map.

Crying Hill overlooks one of the largest

conflicts in Dakota Territory history. In 1863, General Sibley led ~2200

soldiers into Dakota Territory on a punitive campaign from Camp Pope in

Minnesota. The campaign concluded at the mouth of Apple Creek, on Aug. 1, 1863,

when Sibley withdrew from the field of conflict, unable to pursue the Lakȟóta

across the Missouri River. The Húŋkpapȟa, led by Black Eyes, crossed the

Missouri River where the Northern Pacific Railroad Bridge spans the river, and

thence up the Heart River to escape pursuit.

A week after the Apple Creek conflict,

Black Eyes brought the Húŋkpapȟa back across the Missouri River and re-crossed

the Missouri at the northern most mouth of the Heart River (which had three

mouths at that time), and camped above the floodplain opposite Crying Hill.

During the night, miners from Fort Benton, MT came down and camped on a

sandbar. The next morning the miners tried forced themselves on a Lakȟóta woman

who had gone down to the river to refresh herself. She died at the miners’

hands; Black Eyes retaliated and the Húŋkpapȟa warriors awoke and hurried to

the river’s edge and exchanged gunfire with the hostiles. During the fight, the

boat’s swivel gun misfired into the boat itself causing a fire to break out.

The miners were killed to the last man, and there precious gold was scattered

about the sandbar[8].

The Mandan Historical Society features this photo of the "Mandan Hill" in the summer of 1959. Visit the Mandan Historical Society today.

In 1934, a local Boy Scouts troop

arranged forty-seven truckloads of local stone into giant letters which spelled

out “MaNDan,” on what became renamed “Mandan Hill.” It was maintained by the

Boy Scouts, Girl Scouts, and the Mandan Jaycees over the years, then in 1968,

after Interstate 94 (I-94) was complete, the “MaNDan” sign was reconstructed in

concrete. In the late 1990’s, pine trees were planted on the south face of

Crying Hill arranged to spell “MANDAN[9].”

Sometime in 2003, Mr. Patrick Atkinson, acquired

4.7 acres of what remained of Crying Hill, to save it from development.

Atkinson heard that the property was going to be put on the market, and he

dashed up to Crying Hill after hearing a little about the lore, and provoked by

his own winter memories of sledding down the face of Crying Hill. He took his

son to the site to talk about what it meant to them. They concluded to save

what they could. Atkinson maintains that the Crying Hill preservation effort is

ecumenical and non-political, preserving the site for the sake of the

sacredness and inspiration found there by native and non-native alike[10]. Visit Atkinson's site about Crying Hill.

In 2008, Preservation North Dakota

declared that Crying Hill was endangered. To be declared endangered, a site

must be of historical, cultural, or architectural significance and in danger of

demolition, deterioration, or substantial alteration due to neglect or

vandalism. Preservation North Dakota acknowledged the preservation efforts of

Atkinson and the Crying Hill preservation coalition for saving Crying Hill for

the edification and gratification of future citizens.

Dakota Wind is an enrolled member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. He is currently a university student working on a degree in History with a focus on American Indian and Western History. He maintains the history website The First Scout.

Dakota Wind is an enrolled member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. He is currently a university student working on a degree in History with a focus on American Indian and Western History. He maintains the history website The First Scout.

[1] Welch, Alfred, Col. "Good Fur

Blanket Was Mayor Of Mandan In 1738 - Proof Is Found Of Ancient City On Present

Site." Mandan Daily Pioneer

(Mandan), April 14, 1924.

[2] Welch, Alfred, Col. "Joe

Packineau's Verson of The Split and Formation of Crows." Welch Dakota

Papers. November 15, 2011. Accessed August 2, 2017. http://www.welchdakotapapers.com.

[3] Welch, Alfred, Col. "Arikara Hide

Their Sacred Stone From The Sioux." Welch Dakota Papers. November 15,

2011. Accessed August 2, 2017. http://www.welchdakotapapers.com.

[4] Welch, Alfred, Col. "More About

The Two Face Stone." Welch Dakota Papers. November 15, 2011. Accessed

August 2, 2017. http://www.welchdakotapapers.com.

[5] Welch, Alfred, Col. "The Minnitari

Stone." Welch Dakota Papers. November 15, 2011. Accessed August 2, 2017. http://www.welchdakotapapers.com.

[6] Welch, Alfred, Col. "Stone Idol

Creek Journey." Welch Dakota Papers. November 15, 2011. Accessed August 2,

2017. http://www.welchdakotapapers.com.

[7] "Spades Of Workers Rudely Disturb

Last Resting Place Of Ancient Gros Ventres Warriors." Mandan Daily Pioneer

(Mandan), May 11, 1933.

[8] Dakota Wind. “The Apple Creek Fight.” The

First Scout. Nov. 17, 2014. Accessed Aug. 4, 2017. http://thefirstscout.blogspot.com.

[9] "Mandan Hill 501 N Mandan

Ave." Mandan Historical Society. 2006. Accessed August 2, 2017. http://mandanhistory.org.

-%5BFacing--Southwest%5D---Nat'lParkService-SiteSurvey-2010-Fig.2.3.png)

-%5BRockCairnRemains-on-Knoll%5D---Nat'lParkService-SiteSurvey-2010.png)