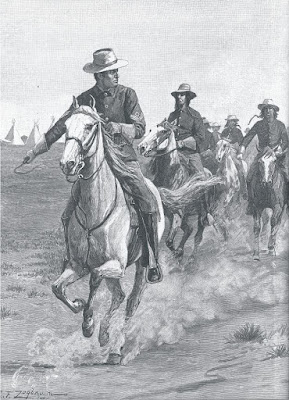

In 1888, Harper's Weekly reported that the US Army was limited by law to 25,000 enlisted service men. The Army was also limited to only 200 Indian scouts. General Miles believed that the Indian scouts were essential to the Army's efforts on the frontier. Wood engraving by RF Zogbaum which appeared in Harper's Weekly, May 1889.

The US Indian Scouts On Expedition

On The Little Bighorn Campaign

By Dakota Wind

MANDAN, N.D. - The scouts who served at Fort Abraham Lincoln were called the Fort McKeen Detachment of Scouts. Most of them were Indian scouts in service in the United States military defending their way of life, that is, that their people could live. Other scouts were contracted civilians, holdovers from the last days of the fur trade era, who could speak the native languages fluently or knew the lay of the land like the back of their hand.

This book was required reading for one of my courses at university. It details the interactions of whites, blacks, and natives leading up to the Revoluntionary War. The English had promised freedom to black slaves who fought for the British. The English and Americans divided several tribes as each country vied for allies during the war. Log onto Amazon or ebay and get yourself a copy.

The history of scouts serving our country goes back to before there even was a United States.Certainly the history of Indians serving our country goes back just as far, and the AmericanRevolution couldn't have been won without Indians aiding the colonials or the colonials adapting the guerilla fighting techniques the Indians favored.

It wasn't until the Civil War that Congress took note of the thousands of Indians who were already fighting for both the North and South, entire companies and commands made up of Indians, including battles fought by Indians, and against Indians (ex. Cabin’s Creek) that Congress recognized the Indians' service by forming an official branch for them, the US Scouts. This new branch of the Army included an official insignia and crossed sabers accompanied by the letters “USS.”

This is the first official insignia worn by the US Scouts. The sabers of this insignia were later replaced by crossed arrows in the mid 1880s.

The Indian scouts who served at Fort Abraham Lincoln began their service at Fort McKeen, a two company infantry post constructed in 1872. Fort Abraham Lincoln, a six company cavalry post, was built a year later on the plains below the infantry post and the new name encompassed both forts. The only thing to retain the name “Fort McKeen” was the detachment of Indian Scouts.

Each detachment of Indian Scouts received their own guidon like this one pictured. Some detachments even had their tribal affiliation on the guidon as well as which territory or fort they served at.

On July 6, 1872, Fred Gerard was hired as an interpreter at Fort McKeen. He held his position until 1882. During his first year he recruited several Arikara scouts from Fort Buford where activity was primarily running down deserters, to Fort McKeen where they engaged the Sioux in several hit-and-run raids. That first year seven Arikara Scouts died. The Post Surgeon remarked “The Indian scouts in the several skirmishes with the Sioux in Oct. and Nov. exhibited instances of the greatest personal bravery and fearlessness.”

General Custer and the Seventh Cavalry engaged in a skirmish on the north bank of the Yellowstone River across from Pompey's Pillar. Sixty-nine years before, the Corps of Discovery came by here and Captain William Clark left his signature on the east side of the pillar. When you visit the Battle of the Little Bighorn, be sure to take in a visit to Pompey's Pillar too. Its about an hour's drive north, just off of Interstate 94.

On August 4, 1873, the Yellowstone Expedition reached the Powder River. About 90 men, including the scouts, explored the Tongue River. There they were surprised when six Sioux men attempted to stampede their horses. The Sioux were driven off and pursued to a heavy stand of trees, when an estimated 300 mounted Sioux warriors led by Chief Gall, burst forth to fight. Bloody Knife was the quickest draw, remarked General Custer, having shot and killed the first antagonist, from horseback. The scouts' bravery and guidance spared all the soldiers' lives but for three.

The Arikara scouts were a conservative lot, who often complained to the chief of scouts, a non- Indian second lieutenant who served as liaison to the commanding officer, about the traffic in flesh the enlisted soldiers partook in. The scouts also had zero tolerance for domestic abuse, and any soldier who was found beating women was arrested immediately.

In his yearly report of 1873, Post Surgeon Middleton praised the service of the scouts, saying, “There have been no successful desertions during the year, although many have attempted it…deserters are easily overtaken by the scouts and [accompanying] detachments.” At some forts, the desertion rate was as high as 30% after many newly enlisted soldiers realized life in the army in the frontier wasn't what they expected. Middleton's acclaim for the scouts pulling military police duty was mirrored throughout Dakota Territory. Simply put, the scouts were at home in a land they were born and raised in, and could read the features of friend or foe in a glance.

The Black Hills Expedition of 1874, led by General Custer, a journey intended to confirm the discovery of gold in the hills, left Fort Abraham Lincoln guided by a detachment of scouts that consisted of 22 Arikara and 38 Santee Dakota Sioux up from Nebraska. There is no written record if the groups socialized, but together they led about 1,200 men to the hills and back, covering nearly 1,200 miles. Professor Donaldson, a geologist on the expedition, remarked, “The scouts are invaluable. Where they scour the country, no ambush could be successfully laid.”

Above is a map of what was then called the "Centennial Campaign."

On May 17, 1876, the Centennial Campaign left Fort Abraham Lincoln with the scouts in lead, guiding about 1200 men to meet their destiny at the Little Big Horn. Twenty-one scouts were left behind at Fort Abraham Lincoln, twelve at Fort Stevenson, and six at Fort Buford to maintain open lines of communication. In all, a total of fifty-one Indian scouts from the Arikara, the Crow, the Sioux, and the Pikuni (also called Piegan or Blackfoot) escorted and safeguarded the 7th Cavalry. Surgeon DeWolf wrote of the scouts, “…we cannot be surprised very easily. The Indian

Scouts are all camped tonight outside us…Scouts working ten miles out.” Indeed, no ambush or raid could be laid.

Approaching the Little Bighorn, General Custer divided his command into three columns. One column was led by Captain Benteen, another by Major Reno, and one by General Custer himself. General Custer recieved a missive from General Terry telling him to engage the Lakota and Cheyenne. The General Terry/General Custer command was supposed to have waited a few more days for General Crook and General Gibbon.

The duty of the scouts was to guide the 7th Cavalry to the encampment of the Sioux and their ally, the Cheyenne. Vacant camps, trails, and other sign of the Sioux encampment lead the Indian scouts to believe there were perhaps five thousand of the enemy. On June 25, 1876, the Crow and Arikara, believing that they were likely seen approaching the Sioux, urged General Custer to engage the enemy immediately if that's what they came out to do, or lose any advantage that surprise would give them. Despite the advice to Custer to immediately go into battle with the Sioux, the scouts didn't seem as excited to fight as the general. Many accounts mention the scouts singing songs, plaiting their hair, painting, etc., not to take their time in meeting the enemy, but because many of them were preparing to meet the creator, as some of them did that day.

The Battle of the Little Big Horn didn't go as General Custer envisioned it would. Instead, a swift and utter downfall met his command. General Custer ordered the Scouts into battle with Major Reno, whose experience fighting the Indians was virtually none, primarily to distract the Sioux on one side so General Custer could flank the Sioux from the north. Dividing his command was a mistake which paved the way for Custer's last stand. Reno's witness to Bloody Knife's sudden death so rattled the Major that he ordered a halt and retreat three times.

Bloody Knife kneels on General Custer's left side and points to a location on a map. Bloody Knife was General Custer's favorite scout. From Bloody Knife, General Custer learned to speak a little Lakota, Arikara, and became well practiced in the Plains Indian sign and gesture language. The two became so close, they regarded one another as brother.

Bob Tailed Bull, Little Soldier, and Bloody Knife lost their lives, two others received wounds, Goose and White Swan, on Major Reno's retreat.

The Battle of the Little Bighorn is often broken down into lines, fights, and skirmishes, with the Last Stand Hill serving as climax. The Arikara and the Lakota regard the Battle of the Greasy Grass, as they regard it, as simply one battle. This author has visited the battle several times, and has heard the Lakota and Cheyenne bristle when they hear “there were no survivors.” For certain there were, for the victors in that fateful battle survived to either fight another battle, return to the reservations, or go to Canada.

Captain Miles Keogh's horse, Comanche, shown here is often regarded as the last survivor of Custer's command at Last Stand Hill. There were perhaps a hundred other horses and even one a yellow bulldog survived. Comanche died fifteen years after the battle and was stuffed. Comanche can be seen today in a glass class at the University of Kansas.

For several years Captain Miles Keogh’s horse was accorded some great degree of respect, almost reverence, even honored with a song by Johnny Horton. Similarly do the Arikara hold Bloody Knife’s horse in high regard. Bloody Knife’s pony was shot and injured at the battle and journeyed over 300 miles back to Fort Berthold where he came to stand outside Bloody Knife’s wife’s, She Owl’s, lodge. After arriving home, Bloody Knife’s buckskin pony lay down and died. The Arikara honored the pony in song. If you, dear reader, are fortunate enough to visit the White Shield pow-wow on the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation in North Dakota, you may hear that song, and if you’re luckier, hear one composed for the scouts, other veteran songs, or even one composed for General Custer.

Bloody Knife on one of his horses on the Yellowstone Expedition.

Whether it was skirmishes at the infantry post, the cavalry post, or on expedition, the Indian scouts were the first in line to defend their charges, but most importantly, they protected our country to ensure that their people would live.

MANDAN, N.D. - The scouts who served at Fort Abraham Lincoln were called the Fort McKeen Detachment of Scouts. Most of them were Indian scouts in service in the United States military defending their way of life, that is, that their people could live. Other scouts were contracted civilians, holdovers from the last days of the fur trade era, who could speak the native languages fluently or knew the lay of the land like the back of their hand.

The history of scouts serving our country goes back to before there even was a United States.Certainly the history of Indians serving our country goes back just as far, and the AmericanRevolution couldn't have been won without Indians aiding the colonials or the colonials adapting the guerilla fighting techniques the Indians favored.

It wasn't until the Civil War that Congress took note of the thousands of Indians who were already fighting for both the North and South, entire companies and commands made up of Indians, including battles fought by Indians, and against Indians (ex. Cabin’s Creek) that Congress recognized the Indians' service by forming an official branch for them, the US Scouts. This new branch of the Army included an official insignia and crossed sabers accompanied by the letters “USS.”

The Indian scouts who served at Fort Abraham Lincoln began their service at Fort McKeen, a two company infantry post constructed in 1872. Fort Abraham Lincoln, a six company cavalry post, was built a year later on the plains below the infantry post and the new name encompassed both forts. The only thing to retain the name “Fort McKeen” was the detachment of Indian Scouts.

On July 6, 1872, Fred Gerard was hired as an interpreter at Fort McKeen. He held his position until 1882. During his first year he recruited several Arikara scouts from Fort Buford where activity was primarily running down deserters, to Fort McKeen where they engaged the Sioux in several hit-and-run raids. That first year seven Arikara Scouts died. The Post Surgeon remarked “The Indian scouts in the several skirmishes with the Sioux in Oct. and Nov. exhibited instances of the greatest personal bravery and fearlessness.”

This image of four Arikara scouts was taken at Fort Abraham Lincoln. Bloody Knife is featured in this image on the far right wearing a shaved horn headdress with eagle feather trailer, a symbol of his chieftainship in the peacekeeping society of the Arikara.

General Custer was well aware of the value of the Indian scouts on the frontier. Oftentimes an Indian scout could get messages and mail through hostile territory where a white soldier or civilian scout could not. The scouts provided General Custer with intelligence, given with respect and varying degrees of awe, and were rewarded with preferential treatment.

Forty Arikara scouts were brought on to guide the military from Fort Abraham Lincoln to the Yellowstone in 1873. Only three civilians joined the Indian scouts to escort twenty companies of the 6th, 8th, 9th, 17th, and 22nd infantry regiments, and ten companies of the 7th Cavalry (about 1500), about 350 Northern Pacific Railway survey crew employees, four scientists, and two members of the British nobility, to Yellowstone country. General Custer often accompanied the Indian scouts.

General Custer was well aware of the value of the Indian scouts on the frontier. Oftentimes an Indian scout could get messages and mail through hostile territory where a white soldier or civilian scout could not. The scouts provided General Custer with intelligence, given with respect and varying degrees of awe, and were rewarded with preferential treatment.

Forty Arikara scouts were brought on to guide the military from Fort Abraham Lincoln to the Yellowstone in 1873. Only three civilians joined the Indian scouts to escort twenty companies of the 6th, 8th, 9th, 17th, and 22nd infantry regiments, and ten companies of the 7th Cavalry (about 1500), about 350 Northern Pacific Railway survey crew employees, four scientists, and two members of the British nobility, to Yellowstone country. General Custer often accompanied the Indian scouts.

On August 4, 1873, the Yellowstone Expedition reached the Powder River. About 90 men, including the scouts, explored the Tongue River. There they were surprised when six Sioux men attempted to stampede their horses. The Sioux were driven off and pursued to a heavy stand of trees, when an estimated 300 mounted Sioux warriors led by Chief Gall, burst forth to fight. Bloody Knife was the quickest draw, remarked General Custer, having shot and killed the first antagonist, from horseback. The scouts' bravery and guidance spared all the soldiers' lives but for three.

The Arikara scouts were a conservative lot, who often complained to the chief of scouts, a non- Indian second lieutenant who served as liaison to the commanding officer, about the traffic in flesh the enlisted soldiers partook in. The scouts also had zero tolerance for domestic abuse, and any soldier who was found beating women was arrested immediately.

In his yearly report of 1873, Post Surgeon Middleton praised the service of the scouts, saying, “There have been no successful desertions during the year, although many have attempted it…deserters are easily overtaken by the scouts and [accompanying] detachments.” At some forts, the desertion rate was as high as 30% after many newly enlisted soldiers realized life in the army in the frontier wasn't what they expected. Middleton's acclaim for the scouts pulling military police duty was mirrored throughout Dakota Territory. Simply put, the scouts were at home in a land they were born and raised in, and could read the features of friend or foe in a glance.

Here's an image of the encampment at the Black Hills. Photo by Illingsworth.

The Black Hills Expedition of 1874, led by General Custer, a journey intended to confirm the discovery of gold in the hills, left Fort Abraham Lincoln guided by a detachment of scouts that consisted of 22 Arikara and 38 Santee Dakota Sioux up from Nebraska. There is no written record if the groups socialized, but together they led about 1,200 men to the hills and back, covering nearly 1,200 miles. Professor Donaldson, a geologist on the expedition, remarked, “The scouts are invaluable. Where they scour the country, no ambush could be successfully laid.”

On May 17, 1876, the Centennial Campaign left Fort Abraham Lincoln with the scouts in lead, guiding about 1200 men to meet their destiny at the Little Big Horn. Twenty-one scouts were left behind at Fort Abraham Lincoln, twelve at Fort Stevenson, and six at Fort Buford to maintain open lines of communication. In all, a total of fifty-one Indian scouts from the Arikara, the Crow, the Sioux, and the Pikuni (also called Piegan or Blackfoot) escorted and safeguarded the 7th Cavalry. Surgeon DeWolf wrote of the scouts, “…we cannot be surprised very easily. The Indian

Scouts are all camped tonight outside us…Scouts working ten miles out.” Indeed, no ambush or raid could be laid.

The duty of the scouts was to guide the 7th Cavalry to the encampment of the Sioux and their ally, the Cheyenne. Vacant camps, trails, and other sign of the Sioux encampment lead the Indian scouts to believe there were perhaps five thousand of the enemy. On June 25, 1876, the Crow and Arikara, believing that they were likely seen approaching the Sioux, urged General Custer to engage the enemy immediately if that's what they came out to do, or lose any advantage that surprise would give them. Despite the advice to Custer to immediately go into battle with the Sioux, the scouts didn't seem as excited to fight as the general. Many accounts mention the scouts singing songs, plaiting their hair, painting, etc., not to take their time in meeting the enemy, but because many of them were preparing to meet the creator, as some of them did that day.

General Custer was attempting to flank the Lakota and Cheyenne from northeast of the encampment. General Custer used this same strategy at Washita where he was outnumbered there as well. That strategy was to capture the women and children who fled opposite from the first attack. The native camp was far larger than General Custer believed it was and his attempt failed.

The scouts didn't have to be at the Battle of the Little Big Horn. Their duty came to an end the moment they ascended the Crow's Nest and directed General Custer to the direction of the Sioux encampment. The scouts voluntarily entered combat against the principles for which they were employed, and they went to take traditional honors by stealing horses from the Sioux and Cheyenne.

General Custer ordered his men to take the higher ground, a last attempt to hold a strategic advantage over the Lakota and Cheyenne when the warriors began to retaliate. Today the hill is called Last Stand Hill. The scouts didn't have to be at the Battle of the Little Big Horn. Their duty came to an end the moment they ascended the Crow's Nest and directed General Custer to the direction of the Sioux encampment. The scouts voluntarily entered combat against the principles for which they were employed, and they went to take traditional honors by stealing horses from the Sioux and Cheyenne.

The Battle of the Little Big Horn didn't go as General Custer envisioned it would. Instead, a swift and utter downfall met his command. General Custer ordered the Scouts into battle with Major Reno, whose experience fighting the Indians was virtually none, primarily to distract the Sioux on one side so General Custer could flank the Sioux from the north. Dividing his command was a mistake which paved the way for Custer's last stand. Reno's witness to Bloody Knife's sudden death so rattled the Major that he ordered a halt and retreat three times.

Bob Tailed Bull, Little Soldier, and Bloody Knife lost their lives, two others received wounds, Goose and White Swan, on Major Reno's retreat.

The Battle of the Little Bighorn is often broken down into lines, fights, and skirmishes, with the Last Stand Hill serving as climax. The Arikara and the Lakota regard the Battle of the Greasy Grass, as they regard it, as simply one battle. This author has visited the battle several times, and has heard the Lakota and Cheyenne bristle when they hear “there were no survivors.” For certain there were, for the victors in that fateful battle survived to either fight another battle, return to the reservations, or go to Canada.

For several years Captain Miles Keogh’s horse was accorded some great degree of respect, almost reverence, even honored with a song by Johnny Horton. Similarly do the Arikara hold Bloody Knife’s horse in high regard. Bloody Knife’s pony was shot and injured at the battle and journeyed over 300 miles back to Fort Berthold where he came to stand outside Bloody Knife’s wife’s, She Owl’s, lodge. After arriving home, Bloody Knife’s buckskin pony lay down and died. The Arikara honored the pony in song. If you, dear reader, are fortunate enough to visit the White Shield pow-wow on the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation in North Dakota, you may hear that song, and if you’re luckier, hear one composed for the scouts, other veteran songs, or even one composed for General Custer.

Whether it was skirmishes at the infantry post, the cavalry post, or on expedition, the Indian scouts were the first in line to defend their charges, but most importantly, they protected our country to ensure that their people would live.

No comments:

Post a Comment