The High Dog Winter Count

History Of The Great Plains

By Dakota Wind

Bismarck,

ND – The High Dog

Winter Count, a pictographic history of the Huŋkphápȟa Lakȟóta

people is on display at the North Dakota Heritage Center. It reaches back to

the year 1798 and concludes in 1912. Šúŋka Waŋkátuya (Lit. Dog On-High), or

High Dog, kept a winter count, a pictographic mnemonic device in which each

year was remembered with one image and a “name.” Years, or winters, were never

numbered.

When the year was named, a collective of

elders, leaders, and medicine people would gather together to determine what to

call the year, sometimes in the spring when the new year began, or sometimes in

the fall or over the winter.

The first entry of the High Dog Winter Count.

High Dog’s winter count echoes content within other winter counts, such as Blue Thunder, No Two Horns, Swift Dog, and Jaw, among others, but it has distinct entries all its own. The first entry of High Dog’s winter count features an image of one man with a “fan” of four very blue feathers fanning or presenting the feathers to another man. Here follows the entry:

High Dog’s winter count echoes content within other winter counts, such as Blue Thunder, No Two Horns, Swift Dog, and Jaw, among others, but it has distinct entries all its own. The first entry of High Dog’s winter count features an image of one man with a “fan” of four very blue feathers fanning or presenting the feathers to another man. Here follows the entry:

Wiyáka tȟotȟó uŋ akíčilowaŋpi (Lit.

Feathers blue-blue to-use-something singing-praise-they). They sang praises

using very blue feathers.

It was agreed to among the people that

any one of the tribe who was seen wearing the blue feathers should be an

example to others in virtue and goodness, and should be esteemed by all as a

guardian of the "nation." Four men at that time were set apart with

the blue feathers.

The feathers that are depicted on High Dog's entry resemble the tail feathers of the Ziŋtkátȟo Glegléğa (lit. “Bird-blue striped-very"), commonly known as the Blue Jay. In particular, this rendering resembles the beautifully blue Stellar’s Jay tail feathers.

The Lakȟóta say that when the Ziŋtkátȟo Glegléğa returns, cold rains follow. Steller's Jay photo by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

The feathers that are depicted on High Dog's entry resemble the tail feathers of the Ziŋtkátȟo Glegléğa (lit. “Bird-blue striped-very"), commonly known as the Blue Jay. In particular, this rendering resembles the beautifully blue Stellar’s Jay tail feathers.

The Lakȟóta say that when the Ziŋtkátȟo Glegléğa returns, cold rains follow. Steller's Jay photo by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

By an old ceremony men were set apart as

“Atéyapi” (Fathers) and women as "Ináyapi" (mothers). By this

ceremony these people were chosen as leaders in the tribe, and their

admonitions were heeded.

Sometimes a small child was raised to

this class because of a portent at his or her birth that indicated his or her

superior wisdom. Grown persons were raised to this class on account of some

distinguished service to the tribe, as well as for manifest wisdom and

foresight in affairs. Those raised to this class while they were babes are said

to have been generally the most satisfactory administrators of justice. Such

children received careful training both from those previously raised to this class

and also from their grandmothers.

They were taught to admonish with

discretion and with gentleness, to honor and respect each and every one of

every age and themselves; to be kind to dogs and all animals. If one of this

class proved unworthy, one was not deposed, but from that time on, or until one

had purged oneself of old offenses and adopted better manners one had small

influence in the council-meetings, yet the people still respected him or her.

At that time, men were gifted with blue feathers to designate their worthiness; women were gifted with blue glass pendants they wore proudly upon their forehead, though this practice has long since faded.

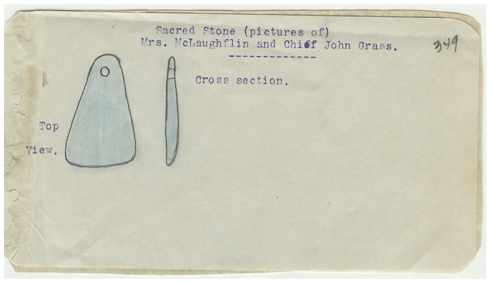

The Blue Cloud Stone as sketched by Col. A. Welch.

Kȟaŋpéska Imánipi Wiŋ (Walking On The Shell Woman), the wife of Matȟó Watȟákpe (Charging Bear; John Grass), was among the last Lakȟóta women to have possessed one of what they called Maȟpíya Tȟó, or a Blue Cloud Stone. The stone was actually a flat blue polished piece of glass, possibly volcanic, which was melted and poured into a sand or clay mold. The stone was made by a woman of virtue, and only one was made in a year.

When it was worn, the woman was held in high esteem by all as good and honorable, a role model for all women

No comments:

Post a Comment