A composite panorama of Apple Creek from the northeast point of Pictured Bluff. The image is southwest (l) to north (r).

The Apple Creek

Conflict 150 Years Later

By Dakota Wind

BISMARCK, N.D. – The Mníšoše, Missouri

River, moves determinedly along the ancient valley it has carved over thousands

of years. The river flows in the very heart of the Great Plains, in fact, aside

from the wind, it’s a defining feature of the prairie steppe. Its Lakȟóta name means “The Water A-stir” in

reference to its muddy stirred up appearance in historic times. Commercial

traffic on the river in the nineteenth century came to call it “The Big Muddy.”

Tȟaspáŋla Wakpála, Apple Creek, meanders along its own course from a field north and east

of present-day Bismarck, N.D. The Menoken Indian Village rests along the quiet

creek, a silent witness to trade in what archaeologists call the Late Woodlands

period. The creek’s name refers to the tree that bears the tiny edible thorn

apple.

Where the Tȟaspáŋla Wakpála converges with Mníšoše is Mayá Itówapi, Pictured Bluff. There, along the bluff are caves

where the sediment is layered in colors. A testament to the changing climate

throughout the ages of the world to the geologist, but to the Lakȟóta, it was a place to gather

natural yellow and red pigments to create paint.

There was a conflict between

the Pȟadáni (Arikara) and the Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋna (Yanktonai) in the 1830’s.

According to the John K. Bear winter count the

year is recorded as Čhaŋnóna na Pȟadáni

ob thi apá kičhízapi, The Wood-Hitters (a band of the Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋna) fought with the Arikara.

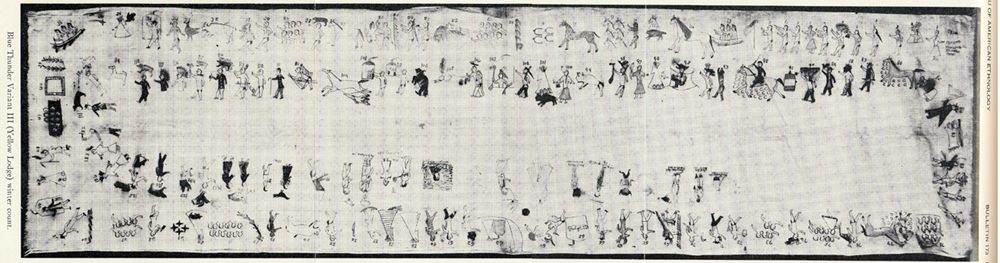

The Blue Thunder Winter Count, variant III.

The Waŋkíya Ťho, Blue Thunder, winter

count correlates this event at a Dakota winter camp located below Čhaŋté Wakpá, Heart River. According to

Blue Thunder, the assailants are variously identified as Arikara, Mandan, or Assiniboine.

The Mandan Indians have the Foolish Woman winter count, and they record that they destroyed fifty lodges. The Tȟatȟaŋka Ska, White Bull, winter count

has that winter as Wičhíyela waníyetu

wičhákasotapi, the Yanktonai were almost wiped out that winter.

The John K. Bear winter

count also mentions the Dakota Conflict in its 1863 entry: Isáŋyatí wašíčuŋ ob okȟíčize, the Santee warred with the whites.

The Minnesota Dakota conflict is also reflected in the Red Horse Owner, Roan

Bear, and Wind winter counts.

Clell Gannon, a depression era artist, painted this scene of General Sibley's command in pursuit of the Sioux. The painting can be found in the south vestibule of the Burleigh County Courthouse, Bismarck, ND.

The fight between the two tribes paled in comparison when in 1863, General Sibley and his command of about four thousand soldiers engaged the Dakȟóta and Lakȟóta people in a running battle lasting two weeks, from Big Mound (near present-day Tappen, N.D.) to Pictured Bluff.

Sitting Bull counts coup on one of Sibley's men and steals a mule at the Big Mound Conflict. The image was Sitting Bull's own account, from "Sitting Bull's Heiroglyphic Autobiography" which appears in Stanley Vestal's "Sitting Bull: Champion Of The Sioux."

In Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake’s, Sitting Bull’s, own pictographic account, he

placed himself at Big Mound where he rode into Sibley’s camp, stole a mule, and

counted coup. It is almost entirely certain that if this great leader was at

the beginning of the running battle, he was there to the end at Pictured Bluff.

The running battle began as

a masterful retreat on July 24, 1863, across hilly terrain in a sinuous line

back and forth across streams. This constant crossing, in effect, caused Sibley

to lag behind enough for the Dakȟóta

and Lakȟóta to gain enough lead time that

the women, children, and elders could navigate their crossing waŋna hiyóȟpayA Tȟaspáŋla Wakpála hená Mníšoše, where the Apple Creek converges

with the Missouri River.

That critical crossing came

on July 29, 1863. The oyáte, people,

abandoned their thiíkčeka, lodges, on

the broad flood plain of the Mníšoše.

A thousand lodges encircled two little lakes, sloughs in later years. They

crossed the Mníšoše in as many as

five places below Pictured Bluff. The warriors rallied together, perhaps under

the leadership of Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake or

Phizí (Gall), and took the high

ground a-top Pictured Bluff.

The women, children, and

elders who made a successful crossing signaled the warriors with flashes of

sunlight using trade mirrors. The warriors in turn, signaled back to their

loved ones then they turned their attention to Sibley’s command. There is no

exact number of warriors, but if there were a thousand lodges, then there was at least one able-bodied man or warrior per lodge. Using this projection, the

warriors were outnumbered four-to-one.

Sibley and his men arrived

on the scene, July 29, 1863, to witness flashes of light in communiqué to those in safety across the river. The general struck camp and

named it “Camp Slaughter” after a doctor in his command. Over the course of the

next few days, Sibley could not take the hill and some of his men were ambushed

in the middle of the night. The morale of his soldiers suffered and on July 31,

withdrew his men from the field when the enemy seemingly disappeared.

The Apple Creek Conflict is

the only fight in the Punitive Campaigns of 1863 & 1864 in which the Dakȟóta and Lakȟóta chose the battlefield, met their aggressor, and held them

off until they withdrew. This clear victory became entirely overshadowed by the

tragedies of Iŋyáŋsaŋ (Whitestone

Hill) and Tȟáȟča Wakútepi (Killdeer),

and the victory of Pȟežísluta, the

Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876.

An unknown, or perhaps forgotten, artist pictographed this scene which was originally identified by Mike Cowdrey as "The Battle Of Whitestone Hill," but is quite possibly a Yanktonai account of the Apple Creek Conflict.

Susan Kelly Power,

an esteemed uŋčí (grandmother) of the

Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋna Dakȟóta and enrolled

member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and great-granddaughter of Chief Two Bear, has the oral tradition that places

three warriors there at the Apple Creek Conflict: Callous Leg, Little Soldier,

and Has Tricks. There must certainly be more warriors and oral traditions

amongst the Iŋyáŋ Wosláta Oyáŋke, the

community of Standing Rock, and others.

Today, a park named for

General Sibley rests virtually where his Camp Slaughter once stood, where some

of the Dakȟóta and Lakȟóta made their crossing. Bismarck

has turned a battlefield into a place of recreation. There is no signage

explaining the name of the park, nor of the conflict.

The landscape has been appropriated

and development has erased the battlefield; Dakȟóta and Lakȟóta oral tradition recalls that the soldiers chased the people

into the river.

On July 29, 2013, 150 years after Sibley’s command withdrew entirely from the Apple Creek Conflict, the anniversary passed in silence.

On July 29, 2013, 150 years after Sibley’s command withdrew entirely from the Apple Creek Conflict, the anniversary passed in silence.

No comments:

Post a Comment