War Correspondence From The Front Line

The Battle Of The Rosebud, 1876

By Dakota Wind

Author and historian, Peter J. Powell collects the Cheyenne oral traditions about the Battle of the Rosebud in his resource "People of the Sacred Mountain." Therein is a story about how a Cheyenne maiden who witnessed her brother fall off his horse during the fight. She promptly jumped on a horse and rose into the crossfire to save him. The Cheyenne refer to the Battle of the Rosebud as "The Girl Who Saved Her Brother Fight."

Author and historian, Jerome Greene also has a wonderful resource utilizing Lakota and Cheyenne oral traditions about the Rosebud, the Battle of the Little Bighorn and other fights in his resource "Lakota and Cheyenne: Indian Views of the Great Sioux War, 1876-1877."

In 1890, Joseph F. Finerty a war correspondent for the Chicago Times, published a collection of his narratives from 1876 through 1879 titled “War-path and Bivouac, or the Conquest of the Sioux.” Here follows an excerpt:

Dawn had not yet begun to tinge the horizon above the eastern bluffs, when every man of the expedition was astir. How it came about, I know not, but, I suppose, each company commander was quietly notified by the headquarter’s orderlies to get under arms. Low cooking fires were allowed to be kindled, so that the men might have coffee before moving farther down the cañon, and every horse and mule was saddled and loaded with military despatch. Finerty notes that the Indians had a feast the night before and that the following morning the Crow were reluctant to go forward to meet the Sioux and Cheyenne, the Shoshone, however, showed some “martial alacrity.” They [the Cavalry and Scouts] got their horses ready, looked to their arms, and, at last, in the dim morning light, a large party left camp and speedily disappeared over the crests of the northern bluffs.

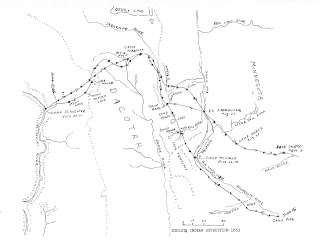

Finerty describes the Infantry moving out with their mules and other equipment. The Cavalry being generally bored and some even taking naps in the saddle until they all began with the “regularity of a machine complicated.” We marched in this fashion, the cavalry finally outstripping the infantry, halting occasionally, until the sun was well above the horizon. At about 8 o’clock, we halted in a valley, very similar in formation to the one in which we had pitched our camp the preceding night. Rosebud stream, indicated by the thick growth of wild roses, or sweet brier, from which its name is derived, flowed sluggishly through it, dividing it from south to north into almost equal parts. Our battalion (Mill’s) occupied the right bank of the creek, with the 2d Cavalry, while on the left bank were the infantry and Henry’s and Van Vliet’s battalions of the 3d Cavalry. The pack train was also on that side of the stream, together with such of the Indians as did not move out before daybreak to look for the Sioux, whom they were by no means anxious to find. The young warriors of the two tribes were running races with their ponies, and the soldiers in their vicinity were enjoying the sport hugely.

At 8:30 o’clock, without any warning, we heard a few shots from behind the bluffs to the north. “They are shooting buffalo over there,” said the Captain [Sutorius]. Very soon we began to know, by the alternate rise and fall of the reports, that the shots were not all fired on one direction. Hardly had we reached this conclusion, when a score or two of our Indian scouts appeared upon the northern crest, and rode down the slopes with incredible speed. “Saddle up, there - saddle up, there, quick!” shouted Colonel Mills, and immediately all the cavalry within sight, without waiting for formal orders, were mounted and ready for action. General Crook, who appreciated the situation, had already ordered the companies of the 4th and 9th Infantry, posted at the foot of the northern slopes, to deploy as skirmishers, leaving their mules with the holders. Hardly had this precaution been taken, when the flying Crow and Snake [Shoshone] scouts, utterly panic stricken, came into camp shouting at the top of their voices, “Heap Sioux! Heap Sioux!” gesticulating wildly in the direction of the bluffs which they had abandoned in such haste. All looked in that direction, and there, sure enough, were the Sioux in goodly numbers, and in loose, but formidable array. The singing of the bullets above our heads speedily convinced us that they had called on business. Finerty doesn’t run out of adjectives to describe the bravery and fortitude of his company; Finerty never holds his callous estimation for the “inferior” race in check, clearly showing present day readers he was a man of his time. “Why the d---l don’t they order us to charge?” asked the brave Von Leutwitz. “Here comes Lemley (the regimental adjutant) now,” answered Sutorius. “How do you feel about it, eh?” he inquired, turning to me. “It is the anniversary of Bunker Hill,” was my answer. “The day of good omen.” “By Jove, I never thought of that,” cried Sutorius, and (loud enough for the soldiers to hear) “It is the anniversary of Bunker Hill, we’re in luck.” The men waved their carbines, but didn’t cheer. Lemley came bounding up on his horse. “The commanding officer’s compliments, Colonel Mill!” he yelled. “Your battalion will charge those bluffs on the center.”

Mills shouted the charge, and Troops A, E, I, and M went to meet the Sioux on the bluff. At about fifty paces the Sioux line broke. When Mills and his troops reached the crest of the bluff, they immediately formed a line. General Crook ordered the 2nd Battalion of the 3rd Cavalry under Col. Guy V. Henry to charge the right flank of the broken Sioux line.

General Crook kept five troops of the 2d Cavalry, under Noyes, in reserve, and ordered Troops C and G of the 3d Cavalry, under Captain Van Vliet and Lieutenant Crawford, to occupy the bluffs on our left rear, so as to check any movement that might be made by the wily enemy from that direction. General Crook estimated that they faced a Sioux force of about 2,500 warriors. The Sioux reformed another line on the second line of heights from Rosebud Creek. Finerty suggests that it was likely Crazy Horse directing and signaling the Sioux with a pocket mirror. Under Crook’s orders, our whole line remounted, and, after another rapid charge, we became masters of the second crest. When we got there, another just like it rose on the other side of the valley. There, too, were the savages, as fresh, apparently, as ever. We dismounted accordingly, and the firing began again. Colonel Mills, who had active charge of our operations, wished to dislodge them. The firefight shifted from Mills’ position to Maj. Evan’s position to the left. Mills led a charge into the valley under cover of the rocky terrain there. The Crow and Shoshone joined the fight led by Maj. Randall. The two bodies of savages, all stripped to the breech-clout, moccasins, and war bonnet, came together in the trough of the valley, the Sioux having descended to meet our allies with right good will. They began a most exciting encounter. Our regulars did not fire because it would have been sure death to some of the friendly Indians, who were barely distinguishable by a red badge which they carried. An Infantryman, Sergeant Van Moll joined the fight. Finerty found it strange that casualties on both sides couldn’t have exceeded more than twenty-five; he also remarks that war cries were constant on both sides. Since this fight was an “Indian” fight, one could safely speculate that the warriors on both sides were fighting for war honors, such as counting coup.

Sergeant Van Moll found himself fighting alone, when the Shoshone and Crow fled from the Sioux. A diminutive Crow scout, “Humpy,” made a bold rescue of Van Moll – and returned to the cheers of all the Cavalry and Scouts.

In order to check the insolence of the Sioux, we were compelled to drive them from the ridge. Colonel Royall met with difficulty on his front. Captain Vroom was deceived by the terrain and became overwhelmed. Lieutenant Foster and Lieutenant Morton, and Captain Andrews (Troop I) extricated Vroom. In repelling the audacions [sic] charge of the Cheyennes upon his battalion, the undaunted Colonel Henry, one of the most accomplished officers in the army, was struck by a bullet, which passed through both cheek bones, broke the bridge of his nose and destroyed the optic nerve in one eye. His orderly, in attempting to assist him, was also wounded, but temporarily blinded as he was, and throwing blood from his mouth by the handful, Henry sat his horse for several minutes in front of the enemy. He finally fell to the ground, and, as that portion of our line, discouraged by the fall of so brave a chief, gave ground a little, the Sioux charged over his prostrate body, but were speedily repelled, and he was happily rescued by some soldiers of his command.

As the day advanced, General Crook became tired of the indecisiveness of the action, and resolved to bring matters to a crisis. He rode up to where the officers of Mill’s battalion were standing, or sitting, behind their men, who were prone to skirmish line, and said, in effect, “It is time to stop this skirmishing, Colonel. You must take your battalion and go for their village away down the cañon.” “All right, sir,” replied Mills, and the order to retire and remount was given. The Indians, thinking we were retreating, became audacious, and fairly hailed bullets after us, wounding several soldiers. Our men, under the eyes of the officers, retired in orderly time, and the whistling of the bullets could not induce them to forget that they were American soldiers. Under such conditions, it was easy to understand how steady discipline can conquer mere numbers.

The bluffs, on both sides of the ravine, were thickly covered with rocks and fir trees, thus affording ample protection to the enemy, and making it impossible for our cavalry to act as flankers. We began to think our force rather weak for so venturous an enterprise, but Lieutenant Bourke informed the colonel [Mills] that the five troops of the 2d Cavalry, under Major Noyes, were marching behind us. A slight rise in the valley enabled us to see the dust stirred up by the supporting columns some distance in the rear.

The day had become absolutely perfect, and we all felt elated, exhilarated as we were by our morning’s experience. Nevertheless, some of the more thoughtful officers has their misgivings, because the cañon was certainly a most dangerous defile, where all the advantage would be on the side of the savages.

Noyes, marching his battalion rapidly, soon overtook our rear guard, and the whole column increased its pace. Fresh signs of Indians began to appear in all directions, and we began to feel that the sighting of their village must be only a question of a few miles further on. We came to a halt in a kind of cross cañon, which had an opening toward the west, and there tightened up our horse girths, and got ready for what we believed must be a desperate fight. Finerty remarked that Gruard’s keen ears heard gunfire toward the “occident.” Major A. H. Nickerson raced to where Colonel Mills and other officers were on the bluffs.

“Mills,”he [Maj. Nickerson] said,”Royall is hard pressed, and must be relieved. Henry is badly wounded, and Vroom’s troop is all cut up. The General orders that you and Noyes defile by your left flank out of this cañon and fall on the rear of the Indians who are pressing Royall.” This, then was the firing that Gruard had heard.

Crook’s order was instantly obeyed, and we were fortunate enough to find a comparatively easy way out of the elongated trap into which duty had led us. We defiled as nearly as possible, by the heads of companies, in parallel columns, so as to carry out the order with greater celerity. They carefully moved around boulders and fallen timbers. When they crested the crown of the plateau, they could hear the attack on Royall’s troop. “Prepare to mount - mount!” shouted the officers, and we were again in the saddle. Then we urged our animals to their best pace, and speedily came in view of the contending parties. The Indians had their ponies, mostly guarded by mere boys, in rear of the low, rocky crest which they occupied. The position held by Royall rose somewhat higher, and both lines could be seen at a glance. There was very heavy firing, and the Sioux were evidently preparing to make an attack in force, as they were riding in by the score, especially from the point abandoned by Mill’s battalion in its movement down the cañon, and which was partially held thereafter by the friendly Indians, a few infantry and a body of sturdy mule packers, commanded by the brave Tom Moore, who fought on that day as if he had been private soldier. Suddenly the Sioux lookouts observed our unexpected approach, and gave the alarm to their friends. We dashed forward at a wild gallop, cheering as we went, and I am sure we were all anxious at that moment to avenge our comrades of Henry’s battalion. But the cunning savages did not wait for us. They picked up their wounded, all but thirteen of their dead, and broke away to the northwest on their fleet ponies, leaving us only the thirteen “scalps,” 150 dead horses and ponies and a few old blankets and war bonnets as trophies of the fray. Our losses, including the friendly Indians, amounted to about fifty, most of the casualties being the 3rd Cavalry, which bore the brunt of the fight on the Rosebud. Thus ended the engagement which was the prelude to the great tragedy that occurred eight days later in the neighboring valley of the Little Big Horn.

According to the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, Finerty was born in Galway, Ireland, 1846, immigrated to the United States in 1864 and immediately enlisted in the Ninety-Ninth Regiment of the New York State Militia. During the “Indian Wars,” Finerty corresponded with at least three newspapers, most often with the Chicago Times, during the “Indian Wars” from 1876-1881. He established his own weekly paper, the Citizen in 1882 and the following year was elected to the Forty-eighth Congress as an Independent Democrat. He died in June of 1908 and was interned in Cavalry Cemetery , Chicago, Ill.

.jpg&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

-%5BFacing--Southwest%5D---Nat'lParkService-SiteSurvey-2010-Fig.2.3.png)

-%5BRockCairnRemains-on-Knoll%5D---Nat'lParkService-SiteSurvey-2010.png)