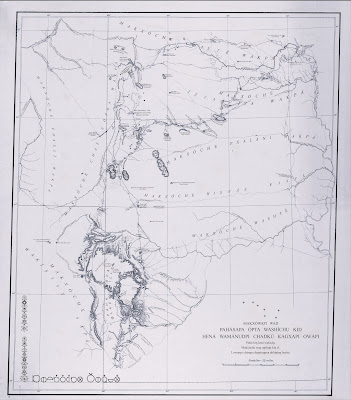

A view of North America from the world view perspective of the Dakhóta-Lakȟóta (Sioux) of the Northern Great Plains.

Makhxóche Washté: The Beautiful CountryA Lakhxóta Landscape Map

By Dakota Wind

Bismarck, ND (TFS) - Sometime in 1932 Cottonwood (Iháŋkthuŋwaŋna, or "Yanktonai;" a division of the Ochéthi Shakówiŋ, or Seven Council Fires, "Great Sioux Nation) and Takes His Shield, (Iháŋkthuŋwaŋna) composed a map testimony of the 1863 Whitestone Hill Massacre.

Bismarck, ND (TFS) - Sometime in 1932 Cottonwood (Iháŋkthuŋwaŋna, or "Yanktonai;" a division of the Ochéthi Shakówiŋ, or Seven Council Fires, "Great Sioux Nation) and Takes His Shield, (Iháŋkthuŋwaŋna) composed a map testimony of the 1863 Whitestone Hill Massacre.

At first glance, the map's "action" details the approach of General Alfred Sully's command from the southwest. By Sully's account, he approached Whitestone Hill from the northwest. If one rotates the map to correct the action so that Sully's approach matches Sully's account, other events on the map become reversed. If one mirrors the map, the map still seems to be incorrect.

A map of the 1863 Whitestone Hill Massacre. For an interpretation of the events on the map visit the Whitestone Hill page at ND Studies. Note: south is at the top.

The Takes His Shield map testimony, composed by Cottonwood, simply taken as it is, it is in fact correct. One needs to change one's worldview orientation, so that the top of the page is south, the bottom of the page is north; left is east, and right is west. It is clear that Takes His Shield and Cottonwood were right all along and that Sully's command does indeed approach them from the northwest. There is no need to manipulate the image.

Years after the spectacular failure of Lt. Col. Custer's campaign at the Little Bighorn conflict, survivors composed their own map testimonies of the fight. There are several, including one attributed to Sitting Bull though it appears to have been drafted by a military hand. Here are a few excerpts of Húŋkpaphxa maps previewed from Mike Donahue's amazing "Drawing Battle Lines." Check your local library, or order yourself a copy.

A Húŋkpaphxa map of the Little Bighorn conflict.

Little Soldier, Húŋkpaphxa, drew this map of the Little Bighorn conflict.

A southern-oriented worldview perspective is represented in the Húŋkpapȟa maps. It is interesting to note that the Húŋkpaphxa show only the camp divisions, not the actual fight. They all demonstrate that the Húŋkpaphxa camp was the one first attacked when Major Reno came calling in the Month of Ripe Chokecherries.

A few years ago, I composed a paper about the 1863 Sibley punitive campaign into Dakota Territory. I interviewed elders and relatives and reconstructed the Apple Creek Fight. I included a directional arrow (pointing north; how colonized of me) with text saying "Wazíyata," or "North." I used Dakhóta and Lakhxóta place names for the rivers and streams, and plateau.

My map of the Apple Creek Fight. 2200 soldiers under Sibley's command against, in his own estimation, 500 warriors on the plateau. It was a conflict bigger than the Little Bighorn.

Afterward, a little kuŋshí (grandmother) from Sisseton, SD, wondered that I since I had put so much work into my paper and map, why did I refer to our country as "Khéya Wíta," or "Turtle Island." Long ago, she said, we called the land and by extension North America, "Makhxóche Washté." I began to do so. If others want to refer to her as Turtle Island, that's okay. On Makhxóche Washté. The Hawk doesn't tell the Western Meadowlark how to hunt or build a nest.

My own map of the waterways on the Northern Great Plains. Thank you Decolonial Atlas for getting me started on this map.

My own map of the waterways on the Northern Great Plains. Thank you Decolonial Atlas for getting me started on this map.

The Lakhxóta word for the south is Itókagxa (Facing-The-Flow-Of-The-Current), or "Facing The Downstream Direction," or simply, "Facing Downstream." In any case, it means looking south. The south-wind is personified in lore as one of five brothers. In some stories, the cardinal directions are spoken of as giants. In one story, the South grapples with the North for control of the plains, which results in summer when the South wins, and winter when the North wins.

The other directions are important too. Ochéthi Shakówiŋ women set up their lodges facing east. When singers begin the Four Directions Song (sometimes Six Directions) they begin facing the west. The fifth and sixth directions are the sky above and the world on which we live. There's also a story of the Seventh Direction, which is the heart.

This brings me to my Lakhxóta map project: Makhxóčhe Washté, The Beautiful Country.

A view of Makhxóche Washté. The Ochéthi Shakówiŋ locations are towards the geographical center of the continent.

I've constructed an interactive map of the Northern Great Plains using place names taken from winter counts, oral traditions, interviews, maps, and books. Some of these place names do not match contemporary place names. Some place names are known by more than one name. Some stream names are not accompanied by "Wakpá," meaning "River," or "Wakpála," meaning "Creek." Some lakes are not accompanied by "Mdé/Bdé/Blé," meaning "Lake." One significant change to the landscape is that it is the Hxahxáwakpa (Mississippi River) that converges with Mníshoshe (the Missouri River). Thinking of it this way, seeing it this way, then it is the Mníshoshe which drains into the Gulf of Mexico.

This map is not complete. If you would like to share a place name with me, I'd be happy to add it and attribute you and your sources.

Here's my Google Map of the Beautiful Country.

Here's my Google Map of the historic reach of bison, signed native languages & Plains Indian Sign, and related Siouan languages.

Makxóche Washté Maps

In the summer of 2022, I began to create a printable map that educators might use in their classrooms. I employed the Txakini orthography but after a series of lengthy discussions with Kevin Locke later that summer, I revisited the map but this time employing the LLC's orthography. I thought to myself that I wasn't hurt in any way using one orthography or another and created a third version of this map this time employing Leroy Curley's beautiful alphabet inspired by the phases of the sun and moon. Here are these maps. I formatted them at 48"x 72" but you can resize them. You could print them in their original size as a poster at Poster Ninja. Please share. These maps are FREE, but if you're so inclined you might send me some mázaska to buy a Coke (I don't drink coffee), Venmo me @Dakota-Goodhouse.

The 1874 Black Hills Expedition

Place and Name 150 Years Later

Download your hi-res copy of this map here.

Dakhota Thamakhoche (Land of the Dakota) Maps

Please visit Marlena Myles's beautiful maps on her Dakota Land Map page.

Líla taŋyáŋ éčaŋu, Misuŋ.

ReplyDeleteWell done, Misun.

Thank you so much for speaking with us today when we met you at the Heritage Center. I'll be sharing your blog site with several friends and family. It is wonderful!

ReplyDeleteThere are some Dakota place names and a map that were drawn by and collected from Dakota Elders in "Where the Waters Gather and the Rivers Meet", by Paul Durand. They mirror some of the Dakota place names recorded by Joseph Nicollet in the map he created of the Hydrographical Basin of the Upper Mississippi. He was French but he did try to use the Indigenous place names in his map, with some interesting spelling choices, or sometimes translated the meaning of the names to French.

ReplyDeleteMarlena Myles, Spirit Lake Dakota Artist has created and published some maps with Dakota place names in the Dakota Tamakoce areas of what colonizers call Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota. https://marlenamyl.es/project/dakota-land-map/

ReplyDeleteHello Friend, I appreciate what you are sharing and I return often to your posts. I'm thinking there should be a book about the James River Valley, et. al., i.e., a photo and history book, since as far as I know none are in publication. I'd intend it to explore, on at least half of the pages, the "pre-history", (since it was only thousands of years as compared to not yet 400 years of European exploration and then exploitation). I want to educate against the culturally held misconception that there was not discernable history before European colonialism. I have experienced Native cultures on at four continents so am not new to this area of study. I would like to sometime discuss your thoughts on a "James" River History project.

ReplyDeleteI appreciate your map of Lakota/Dakota place names, and would want to incorporate that aesthetic into the book I'm imagining. My own family "settled and farmed" here mid-1890's. I'm appalled that that part of my family held such little respect for the native cultures that had lived on the land they farmed and harvested a life and legacy. I hope to hear back from you.