A Visit to Fort Abraham Lincoln

Military History Explored At Historic Site

By Dakota Wind

MANDAN, N.D. - Fort McKeen, infantry post, was established in June, 1872. Companies “B” and “C” of the 6th Infantry and a detachment of Arikara US Indian Scouts under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Daniel Huston were the first to occupy what one year later became Fort Abraham Lincoln.

Of course, long before Fort McKeen

It is clear that this site has been continuously culturally occupied for the past two thousand years, first by the earth mound culture, then the earth lodge culture, and later by the US

I’ve seen for myself, hard core “Lewis and Clarkers” stop here and at the Lewis and Clark Overlook north of the Mandan Indian village, to read passages from Lewis and Clark ’s journals on the day Lewis and Clark stopped there. It is almost like a religious pilgrimage.

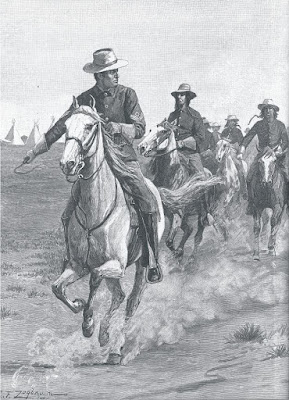

It was determined that the infantry wasn’t the right kind of soldier to protect the Northern Pacific survey line, so Congress established Fort Abraham Lincoln in March of 1873. The fort was home to six companies of the 7th Cavalry. General Custer was stationed here from 1873 to his death at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876.

In 1873, General Custer led his command to the Yellowstone to provide protection to the survey crews from various Sioux attacks.

In 1874, General Custer led his command to the Black Hills to confirm the discovery of gold.

The meanings of building forts in the American west weren’t articulated very well to the Indians or the settlers. For American Indians, forts were a sign of an encroaching domineering society. Fort settlers, forts meant protection from Indians. In hindsight, it is easy to say and agree that forts symbolized the Manifest Destiny policy of the day. A little more difficult to see is the fact that forts didn’t provide protection to settlers at all.

In Libby Custer’s “Boots and Saddles,” she describes the scene about an old man visiting with her husband. The general repeatedly warned him not to “squat” on the west bank; the old man did anyway and was killed by “wild Indians.” The Bismarck Tribune ran a story about the inaction of General Custer and the fort, settlers were angry and scared, but the fort and the soldiers there were not there to protect settlers.

Getting back to what you’ll see at Fort Abraham Lincoln today is a reconstruction of the commanding officer’s quarters as General Custer and his wife would have known it in 1875. My friend and former co-worker, First Sergeant Al Johnson, greets visitors here regularly each summer.

Throughout the house, you’ll see furnishings from the late 19th century to the turn of the century. Really important stuff, like things actually owned by General Custer and his beloved Libby the living history guide will point out to visitors by saying the magic words, “Take special notice of…” That is your cue to express your deepest admiration for the appointed item in the forms of “oohs” and “aahs.” An occasional feigned yawn or laborious stretch and a murmur about the general’s taste works here too.

Take special notice of the burgundy drapes.

Take special notice of the silverware.

You don’t have to take special notice of this commode, but one day someone in a largish group was immediately seized with a sour gut and left a rather unpleasant gift for the next visitors to tour the house. The stench was so pungent and strong and wafted out into the hallway in waves of such sour putrescence one could but barely choke back gags with polite coughs. I share the story here only to notify you dear reader to pay a visit to the latrine and leave your presents there.

Take special notice of the turkey platter.

The cellar. At one point, General Custer kept a bobcat and a porcupine he acquired on the Yellowstone Expedition down there as pets, until he donated them to the University of New York

This drawer and mirror piece was part of General Custer’s and his wife’s personal belongings.

This little marble top table goes with the drawer.

These two chairs were once owned by General Custer. I’m sure that they weren’t artfully arranged for people to look at but used, probably in the study.

This campaign desk was with General Custer throughout the Civil War, his campaign against the KKK in Louisiana

The green cloth bound book titled “Life of Daniel Webster” was given to General Custer by his good friend Lawrence Barrett, a famous Shakespearean actor in New York

If you are so lucky and have the time, First Sergeant Johnson or other guide, can handle the book and show visitors the dedication from Barrett to Custer. The inscription reads, “To. my dear Friend G. A. Custer – from Lawrence Barrett feb 17th 1874.”

Libby’s rocking chair in the main bedroom.

The only other thing that was actually owned by the Custers is the map case on display in the Commissary. The little brass placard on the glass reads, “GA CUSTER’S MAP CASE Libby’s only memento from The Little Bighorn on loan from the trust of Stephen Ronald Cloud Jr. and Ryan John Cloud.” A notarized document testifying the line of ownership back to General Custer has been taped on to the map case.

Thank you to Fort Abraham Lincoln State Park, the greatest park in North Dakota, and First Sergeant Al Johnson, the face of Fort Abraham Lincoln.