The cover features a beautiful scene by American western artist William Jacob Hays, Sr., straight from 1863, and a Karl Bodmer painting of the Mandan Mandeh Pahchu in 1840.

At The Heart Of The World, A Review

Survey History Reveals Native

Homesteads

A Book Review By Dakota Wind

Bismarck, ND – In March 2014, Dr.

Elizabeth Fenn’s seminal work on the history and culture of the Mandan Indians Encounters At The Heart Of The World: A

History Of The Mandan People was published. The following year her work won

the Pulitzer Prize for History.

Fenn is a historian. Naturally, she

meticulously researched the primary resource documents like journals and maps.

She isn’t an archaeologist or a geologist, and she’d be the first to tell you,

but she immersed herself in the surveys, visited many of the sites first-hand,

and then constructed a narrative of her experience of North Dakota making her

research a little more personalized with exposition of the modern landscape,

and produced an amazing piece of history that is easy to read and follow.

In light of the current energy interests

in the Cannonball River vicinity, here follows a ten paragraph excerpt of Encounters At The Heart Of The World

which details some history, geology, and cultural occupation:

A map on page seventeen, one of several appearing in Fenn's book.

THE CANNONBALL RIVER

The Cannonball River starts in Theodore

Roosevelt country – at the edge of the North Dakota badlands where, in the

1880s, the Harvard-trained politician found solace and manhood after personal

tragedy sent him reeling. From here, the stream flows east across 150 miles of

treeless plains and enters the Missouri not far above the South Dakota border.

The confluence is today obscured by the waters of Lake Oahe, but there was a

time when that confluence intrigued nearly every Missouri River traveler.

Scattered along the shoreline and protruding from the banks were hundreds of

stone balls, some as big as two feet in diameter.

These stone balls are the product of the

ancient Fox Hills and Cannonball sandstone formations, deposited by inland seas

that inundated the landscape for nearly half a billion years. Seventy million

years ago, continental uplift caused the waters to recede and the sea floor to

emerge, visible today as undulating plain. By slicing through this surface to

expose the layers of sediment below, the Cannonball River revealed the land’s

ancient, hard-to-fathom aquatic history. The Fox Hills and Cannonball strata

are rich in minerals, especially calcium carbonate – a vestige of marine

animals such as crabs, which often appear fossilized in these formations. When

groundwater flows through the sandstone, the calcium crystallizes with other

minerals and forms concretions – literally concrete – of a spherical shape.

William Clark, who examined the mouth of

the Cannonball as he and Meriwether Lewis headed up the Missouri River on

October 18, 1804, noted that the balls were “of excellent grit for Grindstons.”

His men selected one “to answer for an anker.” The German prince Maximilian of

Weid viewed the distinctive globes from the deck of a steamboat in June 1833,

The Cannonball River “got its name,” he explained, from the “round, yellow

sandstone balls” along its shoreline and that of the Missouri nearby. They were

“perfectly regularly formed, of various sizes: some with a diameter of several

feet, but most of them smaller.” Today, they are little more than a curiosity.

Local residents use them as lawn ornaments.

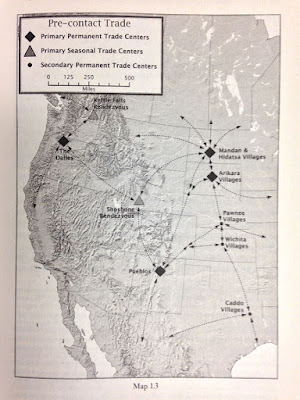

A map from page nineteen detailing continental trade to the Mandan Indian villages. Note: map says "Pre-contact Trade."

AT THE CONFLUENCE OF THE CANNONBALL AND

MISSOURI RIVERS, 1300

For ancestral Mandans, the migration

farther north and the construction of new towns may have mitigated the threat

of violence. Though they fortified some of their new settlements, they built

others in the open, unfortified pattern of old, with fourteen to forty-five

lodges spread over as many as seventeen acres. One such town sat on the south

bank of the Cannonball River where it joins the Missouri, in what is now the

Standing Rock Sioux Reservation.

The South Cannonball villagers tapped a

wide array of food resources. In the short-grass prairies to their west, herds

of bison beckoned hunters. In the mixed- and tall-grass lands across the

Missouri to the east, antelope, deer, and small game did the same. The

riverbanks brimmed with seasonal chokecherries, buffalo berries,

serviceberries, raspberries, plums, and grapes, while river-bottom gardens

produced a bounty of maize, beans, squash, and sunflowers. The Missouri itself

offered catfish, bass, mussels, turtles, waterfowl, and drowned “float” bison,

this last considered particularly delectable.

Much of the South Cannonball village

site has succumbed to the steel plows of more recent farmers tilling the soil

here, but the layout of the ancient village is clear. The settlers dispersed

their town over fifteen acres, with ample space between individual homes. The

houses themselves, about forty in number, were nearly rectangular log-and-earth

structures, narrower at the rear and wider at the front.

There were no fortifications. It appears

that the occupants of the South Cannonball hamlet counted on peaceful relations

with neighboring villagers and with the hunter-gatherers who may have visited

from time to time. But fortified towns nearby suggest that security was tenuous.

South Cannonball may have been on the last villages to follow the scattered

settlement pattern of earlier days. By the mid-1400s, the same neighborhood was

home to some of the most massively defended sites ever seen on the Upper

Missouri River.

Fenn’s narrative reconstructs a historic

Mandan presence in the vicinity of the Cannonball River. Where Dr. W. Ray Wood

focused more on the physicality of the north bank of the Cannonball, Fenn

brings a living history lens to the south bank of the same.

Fenn cares about the people she has

written about, actually making friends on each trip she takes to the Northern

Great Plains. She knows that no matter how carefully she constructed her

narrative, that there would be some among the Mandan who don’t embrace her

interpretation, and she accepts that even as she acknowledges them. She cares

about the history. She cares about the people. Her work reflects that and it is

no wonder her work received such acclaim.

You can get your copy of Fenn’s Encounters At The Heart Of The World: A History

Of The Mandan People at the North Dakota Heritage Center and Museum’s store. The book isn't listed on the website, but its on the floor.

Wonderful book which I return to again and again

ReplyDelete