The Cannonball River looking west of the Albert Grass Memorial Bridge on the Morton-Sioux county line. Photo by author.

The Cannonball-Missouri ConfluenceSite Meets National Historical CriteriaThe Cannonball-Missouri River confluence is host to over a dozen archaeological and historical occupations and events over the course of the past one thousand years. The many documented and verified stories of place meet the qualifications for National Historic Site or National Memorial status. For your consideration, here is a bullet point list to pique your interest followed by a series of figures and narrative expanding on the occupations and events. You can access the complete document here.

by Dakota Wind

* The Ochéti Shakówiŋ (the Great Sioux Nation) and the Late Woodlands Period (circa 500-1000 CE)

* The Mandan Indians and Cannonball River Phase circa 1200-1450 CE

* The Cheyenne Occupation circa 1700-1803 CE

* The Cheyenne-Lakhóta Conflict circa 1762-1763 CE

* Fort Jupiter, an English Trade Post established circa 1798 CE

* The Upper Missouri River intertribal conflicts of the 1790s

* The Corps of Discovery stop in October 1804

* The Historic Spring Flood of 1825

* The Arikara-Lakhóta Conflict of 1835-1836

* The Historic Smallpox Epidemic of 1837

* The Assiniboine-Lakhóta Conflict of 1862-1863

* The Historic Cannonball Ranch circa 1864 through 1913

* The 1864 Punitive Campaign led by General Alfred Sully

* The 1866-1867 winter camp of the Húŋkpapa Lakhóta

Why Is Water So Sacred To The Ochéti Shakówiŋ People?

* The Mandan Indians and Cannonball River Phase circa 1200-1450 CE

* The Cheyenne Occupation circa 1700-1803 CE

* The Cheyenne-Lakhóta Conflict circa 1762-1763 CE

* Fort Jupiter, an English Trade Post established circa 1798 CE

* The Upper Missouri River intertribal conflicts of the 1790s

* The Corps of Discovery stop in October 1804

* The Historic Spring Flood of 1825

* The Arikara-Lakhóta Conflict of 1835-1836

* The Historic Smallpox Epidemic of 1837

* The Assiniboine-Lakhóta Conflict of 1862-1863

* The Historic Cannonball Ranch circa 1864 through 1913

* The 1864 Punitive Campaign led by General Alfred Sully

* The 1866-1867 winter camp of the Húŋkpapa Lakhóta

How Far Back Does The Historic Record Reach?

This pictographic record reaches back to the the Late Woodlands Period (circa 500 CE to 1000 CE) and overlaps with the Cannonball River Phase of Mandan Indian Occupation (circa 1200 CE to 1400 CE).

The Ancestral Ochéti Shakówiŋ Presence

According to Black Elk, when the White Buffalo Calf Woman brought the Gift of the Sacred Pipe, she also gave a sphere of pipestone upon which were carved seven circles representative of the seven rites of prayer. The Seven Medicine Stone Circles at this location also represent these same seven sacred rites.

The Mandan Indians held their annual sundance in this same vicinity when they lived in their Big River Village in the Late Woodland period, or Cannonball River Phase circa 1200 CE. The Cheyenne who came to live on the north bank of the Cannonball River at the turn of 1700 held their annual sundance here until they moved west at the turn of 1800. See figure 16.

The English Came To Trade

Figure 5. Title [Map of Missouri River and vicinity from Saint Charles, Missouri, to Mandan villages of North Dakota: used by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark in their 1804 expedition up Missouri River] (1798). John Evans recorded the Cannonball River as the “Bomb River” on his map of the Missouri River. Evans operated a trading post on the north bank of the Cannonball River in the 1790s. Library of Congress Geography and Map Division Washington, D.C. 20540-4650 USA dcu. Call number G4127.M5 1798 .F5.

The Corps of Discovery Record Their Visit

Figure 6. Title [A map of Lewis and Clark's track, across the western portion of North America from the Mississippi to the Pacific Ocean : by order of the executive of the United States in 1804, 5 & 6] (1814). The Corps of Discovery recorded the Cannonball River on their map. On Oct. 18, 1804, Meriwether Lewis ordered his men to take a cannonball concretion to use as an anchor for their keelboat. Note the historical occupation of the Teton (Lakhóta speaking “Sioux” Indians) in the vicinity of the Cannonball River; the “Saone,” or Saúŋ, was the historic and cultural term for the northern divisions of Teton known today as Húŋkpapa, Mnikówozhu, Itázipcho, and Oóhenuŋpa; the Saúŋ occupied both sides on this stretch of the Missouri River. Library of Congress Geography and Map Division Washington, D.C. 20540-4650 USA dcu. Call number G4126.S12 1814 .L4.

Intertribal Conflict On The Upper Missouri River

Figure 7. The Pictographic Bison Robe, at the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University, MA, details the intertribal conflicts amongst the Arikara, Mandan, Hidstsa, Hunkpapa Lakota, and Iháŋkthuŋwaŋna (Yanktonai) Dakhóta in the Heart River and Cannonball River area along the Missouri River during the 1790s. This same robe details one of many conflicts between the tribes of the Upper Missouri River which concluded in the 1803 Battle of Heart River, which saw the expansion of the Hunkpapa territory. This conflict is remembered in the Drifting Goose Winter Count (aka John K. Bear Winter Count) as Tha Chaŋté Wakpa ed okhíchize, or “There was a battle at Heart River.” The expansion of Húŋkpapa territory north of the Cannonball River is significant. This territorial boundary is recognized in the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty. Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard, MA. Call number PM 99-12-10/53121.

The Cheyenne Start A Fire

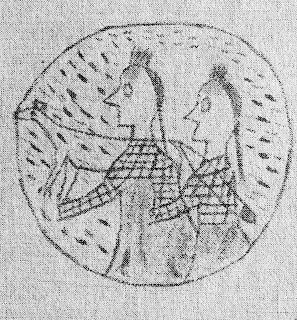

Figure 8. This image represents the intertribal conflict between the Teton Lakhóta and the Cheyenne in the winter of 1762-1763. That year a band of Lakhóta fought the Cheyenne at the mouth of the Cannonball River. The Cheyenne were living on the north bank of the Cannonball River, occupying the same bank and site that the Mandan had previously lived on. The Cheyenne retaliated and set fire to the prairie grass. The Lakhóta sought to outrun the prairie fire and fled up the Long Lake Creek, present-day Badger Creek, located in Emmons County, ND. The fire caught up to the Lakhóta and burned them about their legs, the survivors jumped into Long Lake. When they emerged they became known as Sicháŋgu, or “Burnt Thighs.” The late Albert White Hat Sr. (Rosebud; Sicháŋgu), recalled the oral tradition of the Sicháŋgu as taking place in the Bismarck region. The conflict which resulted in the formation of the Sicháŋgu began at the mouth of the Cannonball River. The identity of one of the tribes of the Ochéti Shakówiŋ tied to this location is significant. Annual report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution (1880), page 692.

The Historic Spring Flood Of 1825

Figure 9. The third entry of the Medicine Bear Winter Count (top row, third from left; #3) recalls 1825 as Mniwíchat'e, or “They drowned.” The Húŋkpapa were camped on the bottomland known as “Gayton’s Crossing,” opposite the mouth of Cannonball River. During the night the ice jam broke and the bottomlands suddenly flooded. They lost about thirty lodges, or about 150 people, and many of their horses to this flood. This event is recorded in other Húŋkpapa and Iháŋkthuŋwaŋna winter counts such as Blue Thunder, Long Soldier, High Dog, No Two Horns, and the Chandler-Porht at the same location. Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, Concord, NH. Call number 2009.65.

Arikara-Lakhóta Trade Ends In Fight

Figure 10. The thirty-fifth entry on the Long Soldier Winter Count recalls the winter of 1835-1836 when the Arikara made camp on the Cannonball River. The Lakhóta went to trade with them for corn, and the Arikara killed six of the Lakota. The lodge in this image represents the immovable camp of the Arikara at the approach of the Lakhóta. National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution. Call number 11/6720.

The Historic Smallpox Epidemic Of 1837

Figure 11. An entry from the Medicine Bear Winter Count which recalls the 1837 smallpox epidemic that swept the Northern Great Plains. Several winter counts recall this year, all with similar depictions of a figure covered in marks like this image above.

The High Dog Winter Count, Blue Thunder Winter Count, and the Long Soldier Winter Count, an interview by Mamie Wade (daughter of pioneer rancher William Wade) of Lakhota elder Annie Sky, and the first-hand story remembered by Annie Sky’s granddaughter Dr. Harriet Sky, the Húnkpapa were camped on the bottomland at the Cannonball-Missouri Confluence when smallpox struck.

The High Dog Winter Count and Blue Thunder Winter Count are in the collections at the State Historical Society of North Dakota. The Medicine Bear Winter Count is in the collections at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. A copy of the Long Soldier Winter Count is available for viewing at the Sitting Bull College Library. Mamie Wade’s interview is available to read in the book Paha Sapa Tawoyake: Wade’s Stories by William Wade.

North Dakota Studies identifies the steamboat St. Peters, a trading vessel, that brought the historic 1837 smallpox epidemic to the Northern Great Plains. Access The 1837 Smallpox Epidemic article.

Assiniboine-Lakhóta Fight Among Sacred Stones

Figure 12. An entry from the Long Soldier Winter Count which recalls the winter of 1862-1863 as the year when twenty Assiniboine came on the warpath, there was a battle at the Cannonball River, and the Assiniboine hid behind the cannonball concretions. The circle tells us that the Assiniboine were surrounded and fired upon. The fox image which overlays the Assiniboine tells us they fought with guile. National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution. Call number 11/6720.

Enter: General Alfred Sully, And The 1864 Campaign

Figure 13. On July 29, 1864, after spending two weeks hastily constructing Fort Rice, General Sully took his command of 2200 soldiers, which included a detachment of Winnebago Indian scouts, and ascended the Cannonball River on the south bank, his punitive campaign on the Isáŋyathi Dakhóta anew. Sully also marched against the Lakhóta (Húŋkpapa, Mnikówozhu, Itázipcho, and Oóhenuŋpa), and Iháŋkthuŋwaŋna Dakota, two Siouan groups who had nothing to do with the 1862 Minnesota Dakhóta Conflict. Sully received a dispatch from Fort Rice at midnight on July 22 that the Dakȟóta were on the Knife River. The next day Sully’s command crossed the Cannonball River near present-day communities of Porcupine and Shields, ND. Capt. Seth Eastman, Fort Rice (1864). https://history.army.mil/html/artphoto/pripos/eastman.html

Figure 12. An entry from the Long Soldier Winter Count which recalls the winter of 1862-1863 as the year when twenty Assiniboine came on the warpath, there was a battle at the Cannonball River, and the Assiniboine hid behind the cannonball concretions. The circle tells us that the Assiniboine were surrounded and fired upon. The fox image which overlays the Assiniboine tells us they fought with guile. National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution. Call number 11/6720.

Enter: General Alfred Sully, And The 1864 Campaign

Figure 13. On July 29, 1864, after spending two weeks hastily constructing Fort Rice, General Sully took his command of 2200 soldiers, which included a detachment of Winnebago Indian scouts, and ascended the Cannonball River on the south bank, his punitive campaign on the Isáŋyathi Dakhóta anew. Sully also marched against the Lakhóta (Húŋkpapa, Mnikówozhu, Itázipcho, and Oóhenuŋpa), and Iháŋkthuŋwaŋna Dakota, two Siouan groups who had nothing to do with the 1862 Minnesota Dakhóta Conflict. Sully received a dispatch from Fort Rice at midnight on July 22 that the Dakȟóta were on the Knife River. The next day Sully’s command crossed the Cannonball River near present-day communities of Porcupine and Shields, ND. Capt. Seth Eastman, Fort Rice (1864). https://history.army.mil/html/artphoto/pripos/eastman.html

1864 Campaign Began At Cannonball River

Figure 14. Map of General Alfred Sully’s 1864 punitive campaign in Dakota Territory. Rev. Louis Pfaller, O.S.B., from Capt. H. von Mindon of Sully’s Northwest Expedition. Sully’s Expedition of 1864 featuring the Battles of Killdeer Mountain and the Badlands Battles. https://www.history.nd.gov/pdf/Sully%201864%20by%20Pfaller1.pdf. Pages 24 & 25.

Wounded Leader Walks To Winter Camp At Cannonball

Figure 15. An entry from the Long Soldier Winter Count indicates that the Húŋkpapa were camped at the Cannonball River in 1866-67. Gall was taken by soldiers that winter to Fort Berthold where they stabbed him. Gall was left for dead and the camp moved on. What makes this tale remarkable is that Gall walked to the Húŋkpapa camp at the Cannonball River and recovered. He later fought at the Battle of the Little Bighorn. National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution. Call number 11/6720.

The Historic Cannonball Ranch

Figure 16. In 1999, the Cannonball Ranch was inducted into the North Dakota Cowboy Hall of Fame. It’s one of the oldest ranches in North Dakota. According to the ND Cowboy of Fame, the ranch served as a gathering point as early as 1865. The ranch included a hotel, a general store, a ferry crossing, a steamboat landing and fueling station, a military telegraph station for Fort Rice, and a stage line to the Black Hills in the 1870’s and 1880s. The ranch also included two houses, a barn, a blacksmith shop, a bunk-house, an ice house, a laundry, and tennis court.

The North Dakota Cowboy Hall of Fame’s strict criteria for eligibility to be recognized is that a ranch must have been “instrumental in creating or developing the ranching business, traditions, and lifestyles of North Dakota’s western heritage and livestock industry.”

State Historical Society of North Dakota (1952-00057). Frank B. Fiske Photograph Collection 1952. Call number 958906935.

An Archaeologist Makes An Observation

Figure 17. An aerial perspective of the north bank of the Cannonball River looking southwest. The Mandan Indian village (circa 1250 to 1400) is visible. The DAPL drill pad and earthen fort was erected on this site in 2016. According to the late Dr. Ray Wood, a world-renowned Missouri River archaeologist, John Evans trade post also occupied this locale. Evan referred to this site as “Jupiter’s Fort.” Prologue to Lewis and Clark: The MacKay and Evans Expeditions, University of Oklahoma Press; Norman, OK. 2003. Page 111. Photo by Ray Wood (1955), State Historical Society of North Dakota.

Village, Camp, Sundance, And Internment

Figure 18. The bluff in section 10 of this map is the location of the Mandan Indian village. Section 9 is the location of the historic Cannonball Ranch. Section 15 & 16 is the location of the winter camp of the Húŋkpapa people; it was the location some summers where they had sundance. This floodplain is where the Húŋkpapa, buried an estimated 150 people who drowned in the spring flood of 1825.

Historic Spring Flood Of 1825 Remembered

Figure 19. The highlighted area on the eastern floodplain of the historic Missouri River is where the Iháŋkthuŋwaŋna camped in the winter of 1824-1825. In 1878, the Húŋkpapa chief, Ishtá Sápa (“Black Eye/s”), met with William Wade, a cattle rancher on the Cannonball River, and shared this about the terrible 1825 flood: “...we camped on this bottom land just below here...it was the Wolf Month [February] and it had been warm for a long time. One night the water started coming in over the ground from the river and before we could get to higher ground we were surrounded by water and ice chunks. Our only chance was to get to high ground before we would all be covered up with water. We tried to carry our tepees and supplies but finally had to leave them and many of the women were drowned trying to save their children. Most all our old people drowned and many others. Most all our horses went under and you can still see their heads (skulls) laying [sic] along at the foot of the hills after so many, many years. Two Bears (Mathó Núŋpa) a Yankton chief [sic], saved the lives of several women and children by carrying them from camp to the higher ground.”

The people were buried where they drowned. The line of horses were buried in a line where they were picketed. The area that Two Bears refers to is known to locals now as Etú Phá Shúŋg T’á, or “Dead Horse Head Point.” The northeast quarter of section 22 is called “The Point,” where locals once gathered on the bank overlooking the place where their relatives and horses were laid to rest.

Archaeologist Identifies Another Source

Figure 20. A screen capture of an email sent to then ND State Archaeologist Mr. Paul Picha regarding missing information in the DAPL Class III survey. Mr. Picha not only confirmed the missing information but included another source regarding the 1825 spring flood. The narrative that Mr. Picha pushed that there is nothing there is false. Picha is aware of people and horses buried at this location following this flood.

President Extends Reservation

Figure 21. On March 16, 1875, President Grant extended the boundary of the Standing Rock Sioux Indian Reservation east of the Missouri River along Beaver Creek to the fork of South Beaver Creek then a straight line south to the Iháŋkthuŋwaŋna reservation. The Iháŋkthuŋwaŋna reservation was established by President Grant’s executive order the same day Standing Rock was extended. U.S. General Land Office, Dakota Territory, 1876.

The Three Star Reservation

Figure 22. The Standing Rock Sioux Indian Reservation in Sioux County and Emmons County, North Dakota. This map is based on the 1876 General Land Office Map with President Grant’s executive order. About 628 square miles were added to the Standing Rock Agency. According to Mr. Robert Taken Alive, the Standing Rock extension on the east side of the Missouri River was known as the “Three Star Reservation,” recollection of a personal interview with “Old Man Stretches,” Aug. 1991. The term “Three Star” may be a reference to Major General George Crook. Map by author.

The land east of the Missouri was never ceded nor a treaty signed. President Cleveland signed the 1889 Indian Appropriations Act into law and opened "unassigned" lands for sale to settlers under tenants of the 1863 Homestead Act.

Territory Determined By Tribes Changed By Congress

Figure 23. Jesuit missionary Fr. Pierre-Jean De Smet, who served as a translator at the 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty, drew a map by hand demarcating the boundaries of the Thíthuŋwaŋ Lakhóta which extended to the Heart River. Map of the upper Great Plains and Rocky Mountains region, 1851. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gmd/g4050.ct000883. Call number 2005630226.

.jpg)

.jpg)