Kevin Locke shares the background of some of the oldest flutes in his collection.

Flute Tradition Returns With The Spring

Practice Nearly Faded Away

By Dakota Wind

Standing Rock, N.D. & S.D. - Dawn hit theLand

of Sky and Wind, the Land of Standing Rock

Standing Rock, N.D. & S.D. - Dawn hit the

I pulled up to Solen

High School Northern Great

Plains , and its growing revival.

Rich Dubé, came down from the great snows of Saskatoon , Saskatchewan Saskatoon ,

and was coming down to the Land

of Sky

Naturally, I thought Dubé was going to be a member of the

White Cap Dakota Nation who reside on a reserve just south of Saskatoon . Not that skin color matters but I

was expecting to meet a native man. Who met me instead, and broke my prejudice,

was an impeccable skinny white guy. He seemed used to native scrutiny however

and graciously anticipated and answered my probing questions, which eased my

mental lockjaw. I backed off when I was satisfied that he knew what he was

about.

Dubé had never heard of the native flute until he attended a session for choir teachers...

Dubé had never heard of the native flute until he attended a session for choir teachers...

Dubé is a music teacher. His story with the native flute

begins about ten years ago in Saskatoon .

He was teaching native youth in an inner city music program. Dubé had never

heard of the native flute until he attended a session for choir teachers and he

leafed through a book by Bryan Burton called Voices of the Wind which had

native flute songs transcribed for the recorder. He was looking for something

to capture the interest and inspire his senior kids and thought the native

flute would be much more appealing to his students than just trying to play the

songs on a recorder, a western European instrument.

The music teacher searched the internet looking for flute

makers, and experimenting with various flute kits, discarding those that didn’t

seem to have a true sound to his sharp ears. Eventually, Dubé crossed paths

with Kevin Locke . Kevin sent Dubé

the schematics of one of his great-grandfather’s flutes. Dubé seized the

opportunity to reconstruct not just a traditional flute, but a traditional

flute with the original sound.

One of Dubé's flutes.

Dubé created a cast using the original traditional flute

from Kevin’s schematics. Dubé wanted to create a flute that was easily

constructed and mass produced yet true to the original sound. In the end, his

experiments found success in a custom size ABS plastic flute matching the exact

sound of the original one-hundred twenty-year-old flute.

...small town pride in the class B team that represented the best hopes of the community...

...small town pride in the class B team that represented the best hopes of the community...

I entered the high school and remembered my days when my

team played the Solen Sioux. There was the typical small town pride in the

class B team that represented the best hopes of the community, and like any

small town, the team was fiercely held high in respect. Putting the games of

yesteryear firmly in the back of my head I made my way down the hall towards

the gym where Dubé was preparing his workshop.

Dubé’s luggage was opened up on the bleachers and inside it

was as though he had brought an entire workshop. Someone had set up some tables

and Dubé was quick to set drills, tools and all his accoutrements out for the

workshop. In the span of twenty minutes he trained staff and volunteers in

preparation for students to drill the holes of their flutes.

Kevin arrived about fifteen minutes after we got to the

school. Students were quietly milling about in the halls in eager anticipation

of the morning’s project. A few had poked their heads into the gym to watch

Dubé set up and train the school staff. A teacher, possibly the principle,

cheerfully made some announcements about lunch and stuff before she gently

reminded students to be on their best behavior for Dubé’s flute workshop.

About fifty-five high school students filed into the gym,

arranged by year, and immediately staked out spots on the basketball court. The

gym quickly filled with echoes of growing chatter which became a loud buzz with

the arrival of fifth and sixth graders from the nearby community of Cannonball,

who took the floor closest to where Dubé was set up.

The principle made a few announcements reiterating students

to be on their best behavior and extended a welcome on behalf of the schools

and introduced Kevin. Kevin introduced Dubé who shared some technical things

about the flute and what to be expected in the workshop, and the students

listened as best as students could while they itched to get to the construction.

Dubé divided the large group into three and subdivided each

of those into three at each table. From the time of Dubé’s beginning

instructions to the last student drilling the last hole in the last flute and

the last student assembling the various pieces into a replica of the Lakota

Grandfather flute, about forty minutes had passed. At one point in the assembly

Kevin remarked, “Rich is really organized,” a sentiment which was repeated by

high school staff.

When the last flute was put together, Dubé called for the

students to gather together once again on the basketball court where he offered

some basic flute instruction. It was this instruction that Dubé’s experience as

music teacher came out. When the students were quieted with their flutes and

ready to play, Dubé played a few simple songs with the students who echoed his

rendition of the old English tune “Hot Cross Buns.” The fifth and sixth grade

students were quite familiar with playing the song on their recorders and

followed Dubé’s instruction swiftly.

There, Kevin shared the story of the first flute.

There, Kevin shared the story of the first flute.

After Dubé’s crash course in flute basics, Kevin stepped in

and shared a few flute songs, one of which was the Flag song which the students

recognized right away. The students had grown tired of the floor towards the

end of the workshop and took to the bleachers on the other side of the gym

after the song. There, Kevin shared the story of the first flute. He played the

first flute song as part the story, and sang the song at the end.

One of the things that Kevin shared, a traditional belief,

was that the Dakota and Lakota people are people of the wind. On the tips of

ones fingers are what we call fingerprints. We all have fingerprints. For the

Dakota and Lakota people however, fingerprints are more than something that

identifies and/or incriminates a person, they say that the patterns tell one

which direction the winds were blowing on the day of one’s birth.

In the days of warriors and legend, the flute was played by

young men in traditional courtship, to win the heart of a particular young

woman. A young man might sit outside the lodge of a young woman and serenade

her. If he was successful, she might contrive an excuse to fetch water or

gather additional firewood to spend a few moments with a suitor.

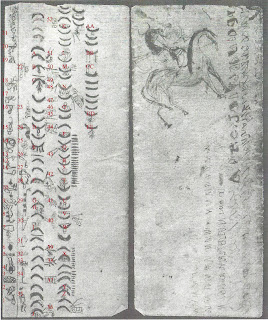

"Indian Courting" by Captain Seth Eastman, 1852.

The flute was a part of daily life.

The flute was a part of daily life. Early American Western

artists like Seth Eastman and George Catlin painted scenes of young men playing

the flute. When the post reservation era began, traditional courtship faded and

was nearly forgotten.

In the 1970s, Kevin Locke

took up the flute and learned about the tradition from men like Richard Fool

Bull, William Horn Cloud, Joseph Rockboy, Asa Primeaux, Henry Crow Dog,

Bill Black Lance, Charles Wise Spirit and Pete Looking Horse among many others.

At a wacipi, Locke saw Richard Fool Bull’s display of flutes and remarked,

“Someone should learn this tradition,” to which Fool Bull said, “Maybe you

should.” And Kevin did.

Locke hopes to pass on the flute tradition to the today’s

generation. Dubé’s flute workshop fits snugly into the world of the young

native student. An individual can construct a flute with traditional specs and

a faithful sound and be finished in five minutes using Dubé’s kit. In a world

where studies come first, where extracurricular activities play a large role in

a student’s life and where popular media influences style and dress, there’s

still time and place for dancers and singers to hit the pow-wow circuit.

In the Land

of Sky

Visit Kevin Locke online at Kevin Locke.

Visit Rich Dubé at Northern Spirit Flutes.