Photo Essay Of Skirmish Site & Little Bighorn Battlefield

Theodore Roosevelt National Park & Ft. Abercrombie

By Dakota Wind

GREAT PLAINS - About five miles south of Fort Abraham Lincoln State Park is the original boundary of the Fort Abraham Lincoln military reservation along a little creek which converges with the Missouri River. In the middle distance of the picture, close to where the bush and scrub line is, is that creek. The Lakota had launched a ten day siege on Fort Rice back in 1868, a smaller less-organized war party had attempted to do the same on Fort Abraham Lincoln in 1873. The field in the picture is privately owned (see image above), but the creek is property of the US Army Corps of Engineers. There is no signage to mark the skirmish, but it is right off of HWY 1806, five miles south of Fort Abraham Lincoln State Park.

Painted Canyon (see above) lies west of Dickinson, ND on I-90, out by Theodore Roosevelt National Park. The canyon is as old as the Grand Canyon, but not nearly as large or well known. If you ever get a chance to visit North Dakota, take in a visit to this geophysical site and experience the mystery of creation. I felt a vast serenity and immense solitude on my early morning visit here.

Another view of Painted Canyon (above).

About fourteen miles easterly of the Little Bighorn Battlefield is "The Crow's Nest," (above) in the distance near the center of the photo. The Crow and Arikara scouts told General Custer that there were more Indians than bullets, and they also advised him to attack immediately while they had the element of surprise. The General waited for about three hours instead, much to the disgust of the scouts.

In roughly the center of this picture (above) is where Major Reno began his engagement with the Hunkpapa Lakota (Teton). Major Reno was an officer used to office work, and had no experience fighting Indians. General Custer divided his command into three with himself leading one third, Major Reno leading a third to make the first attack, and Captain Benteen who lead the last third - the pack train. Reno's attack was to draw the warriors south, the women and children of the Lakota and Cheyenne fled north, General Custer was to flank the encampment from the north - where the women and children were fleeing to, but the encampment was larger than he anticipated. This actually was the same strategy that General Custer employed at Washita, in Oklahoma, where he was also outnumbered. When he captured the women and children there, the fight ended, but it ended with the deaths, a massacre, of Cheyenne women and children. But that's a tale for another day.

Here's the timber line (above) where the Hunkpapa Lakota, led in a counter attack by Chief Gall, retaliated and pushed back Major Reno and his command. Chief Gall, Pizi Intancan, had stepped away from his wife and children, as he did so, they were shot by the soldiers in Reno's command. Among the first, if not the very first of Reno's command to be killed in retaliation, was Bloody Knife. Gall, or Pizi, and Bloody Knife, known to the Lakota as "Tamina Wewe," were lifelong adversaries who grew up in the same Hunkpapa encampment.

The Little Bighorn River, or creek if you prefer (above). Major Reno witnessed the end of Bloody Knife in a way that probably haunted him the rest of his life. Bloody Knife rode in with Reno against the Hunkpapa Lakota and was promptly shot in the head, his brains and blood spattered onto Reno's face. Reno was so rattled that he called for his men to mount and dismount three times before their retreat. Reno's and his men's retreat took them across this part of the Little Bighorn River, and up the embankment towards where I standing when I snapped this photo.

After Reno's retreat, the entire encampment of Lakota and Cheyenne followed General Custer's command to this site, Last Stand Hill (above). General Custer failed to capture any women and children, the encampment was far larger than he thought, and tactics dictated that he ascend the highest point of battle for any advantage, however slight. He and his entire command were killed to the man. The warriors took the hill using three tactics at once: some warriors rode around the hill and me (as seen in many movies), some rode directly through the soldiers to count coup or take them out, yet others shot their arrows up and over the circle of riding warriors and into the soldiers on the hill - according to Wooden Leg, a Northern Cheyenne, it literally rained arrows, and the dust kicked up by the horses turned day to night.

During and after the fight at Last Stand Hill, some Lakota continued to harass Reno and his command. A Lakota sharpshooter took shelter from the top of this hill (above) and proceeded to pick off soldiers who were trying to dig a shelter and assemble a makeshift field hospital. The Lakota Akicita nearly took out a line of soldiers before being shot himself.

Here are the Bighorn Mountains to the south and west of Little Bighorn Battlefield (above). The Lakota and Cheyenne encampment broke the day after the Battle of the Greasy Grass and moved across this plain below. To the Crow and survivors who witnessed the camp break, the movement was awe inspiring. Nothing has been seen like that since.

Captain Weir came a day after the camp breakup and took a survey of the battlefield from this point, today called Weir Point (above). I took this picture looking south to the Reno-Benteen site.

From the same spot, I simply turned northerly to face the Last Stand Hill (above), which I tried to center in this photo. I have a higher resolution of this image, but I couldn't post it here - too big.

On the drive north from Weir Point to Last Stand Hill I encountered some ponies on the privately owned part of the battlefield (above). The Real Bird family on the Crow Indian Reservation put on a reenactment of the battle each year on their land on the battlefield. I've only seen parts of it, but I'm sure that some day I'll catch the whole thing. My reenactor friend, Mr. Stephen Alexander (the world's foremost Custer living historian), has invited me to participate in killing Custer (him) one day and then dying beside him the next. As a native, I'm part of a very select few who could do this. I might take him up on killing him one day, figuratively speaking of course.

The horses are acclimated to the heavy traffic from visitors to the battlefield. I got within five feet of this recently born foal (above). The mare "whuffed" at me and stepped over to me and brought her head to my outstretched hand.

About a hundred paces north of the 7th Cavalry monument is the American Indian monument (above). It lists the tribes and bands who fought to defend their way of life at the battle. The tribes who participated in the battle are the Lakota, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Crow, Arikara, and Blackfeet.

Here's a close up of the metal sculpture (above), a beautiful open representation of Northern Plains Indian pictography. I learned that the Cheyenne have a different name for the battle. They refer to it as "The Battle where the girl rescued her brother." According to one an oral tradition, a boy or young man was unhorsed at the battle. The girl, or young woman, jumped onto a horse and raced into the fight to get him, and she did.

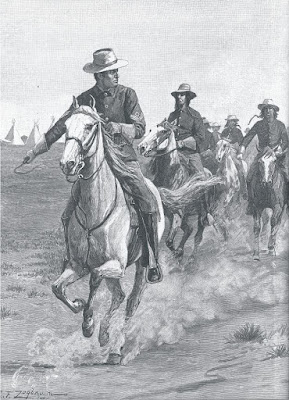

A few days later, I was at Fort Abercrombie south of Fargo, ND about twenty miles, on the day of the 135th anniversary of the Battle of the Little Bighorn (above). After the battle, Co. F of the 7th Cavalry, was brought to Fort Abercrombie. A group of reenactors of the 7th Cavalry were there.

South of Mandan, ND about thirty miles on HWY 1806, is this interesting geophysical feature (above). It has at least four names I've heard, but my favorite is "Rain In The Face Butte." I took a long-time friend of mine down to Cannonball once and on our way I pointed this out on our drive. I told him that the Indians believe that this face looks up into the heavens to the face thats on Mars. I was so serious about it, and his reaction was a mix of confusion and wonder, that I waited a minute to tell him I was pulling his leg. The butte does resemble the profile of a person looking up though, and probably not to Mars.